Table of Contents

Who Was Michelangelo?

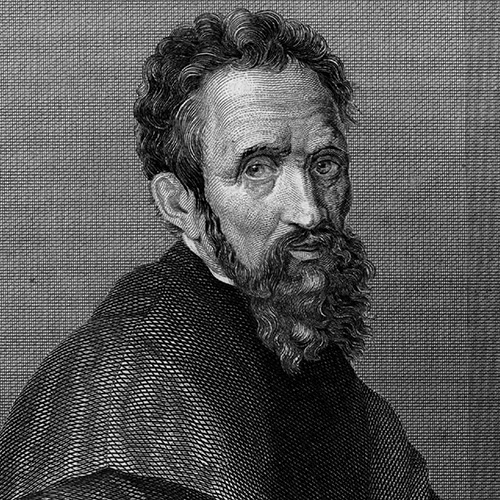

Michelangelo Buonarroti was a multifaceted artist renowned as a painter, sculptor, architect, and poet, and he is widely regarded as one of the most exceptional figures of the Italian Renaissance. His artistic journey began as an apprentice to a painter, followed by his studies in the sculpture gardens of the influential Medici family.

Michelangelo’s career was marked by extraordinary achievements and acclaim during his lifetime, celebrated for his unparalleled artistic virtuosity. Although he always identified as a Florentine, he spent the majority of his life in Rome, where he ultimately passed away at the age of 88. His legacy endures, influencing countless generations of artists and shaping the course of Western art.

Early Life

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, as the second of five sons. At the time of his birth, his father, Leonardo di Buonarrota Simoni, was serving as a magistrate in this small village. The family returned to Florence while Michelangelo was still an infant.

Due to his mother, Francesca Neri, suffering from illness, Michelangelo was placed in the care of a family of stonecutters. He would later quip, “With my wet-nurse’s milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues,” indicating his early immersion in the craft of stonework.

Education

From a young age, Michelangelo displayed a greater fascination for the artistic world around him than for formal schooling. His earliest biographers, including Giorgio Vasari, Ascanio Condivi, and Francesco Varchi, noted his penchant for observing the painters at nearby churches and sketching what he saw. It was likely his grammar school friend, Francesco Granacci, who introduced him to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, an influential figure in Michelangelo’s early development.

Recognizing his son’s lack of interest in the family’s financial endeavors, Michelangelo’s father consented to an apprenticeship for him at the age of 13 in Ghirlandaio’s prestigious workshop. This experience proved pivotal, as it exposed Michelangelo to the technique of fresco—a method of mural painting that involves applying pigment directly to freshly laid wet lime plaster.

Medici Family

From 1489 to 1492, Michelangelo Buonarroti was privileged to study classical sculpture in the gardens of the palace belonging to Lorenzo de’ Medici, a prominent ruler of Florence and a key figure in the influential Medici family. This exceptional opportunity arose after Michelangelo spent just a year under the tutelage of Domenico Ghirlandaio, who recognized the young artist’s potential and recommended him for the position.

During this formative period, Michelangelo gained access to the social elite of Florence, which allowed him to study under the esteemed sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni. He was also exposed to a vibrant intellectual environment, interacting with prominent poets, scholars, and learned humanists. Additionally, he received special permission from the Catholic Church to study cadavers, enhancing his understanding of human anatomy, despite the adverse health effects that such exposure caused him.

These diverse influences laid the foundation for what would become Michelangelo’s signature style, characterized by muscular precision and a lyrical beauty. His early works, including the relief sculptures “Battle of the Centaurs” and “Madonna Seated on a Step,” serve as testaments to his remarkable talent, evident even at the age of 16.

Move to Rome

Political upheaval following the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici compelled Michelangelo to seek refuge in Bologna, where he continued his artistic studies. He returned to Florence in 1495, embarking on his career as a sculptor and drawing inspiration from the masterpieces of classical antiquity.

An intriguing anecdote surrounds Michelangelo’s celebrated “Cupid” sculpture, which was deceptively “aged” to resemble an antique. One version of the story suggests that Michelangelo himself aged the statue to achieve a specific patina, while another version claims that his art dealer buried the sculpture as part of the “aging” process before attempting to sell it as an antique. Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio purchased the “Cupid,” believing it to be a genuine artifact. Upon discovering the ruse, he demanded a refund. However, in an unexpected turn of events, Riario was so impressed with Michelangelo’s artistry that he allowed the artist to keep the payment and subsequently invited him to Rome, where Michelangelo would spend the remainder of his life.

Personality

Despite Michelangelo’s exceptional intellect and abundant talents, which garnered him the respect and patronage of some of Italy’s wealthiest individuals, he was not without his critics. His contentious nature and quick temper often led to strained relationships, particularly with those in positions of authority. This tendency not only resulted in frequent conflicts but also fostered a sense of dissatisfaction within Michelangelo, who was perpetually striving for perfection yet struggled to make compromises.

At times, he experienced spells of melancholy, as reflected in his writings. He expressed a profound sense of distress, stating, “I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts.”

In his youth, Michelangelo suffered a disfiguring blow to the nose after taunting a fellow student, a reminder of his fiery temperament. Over the years, he endured various physical ailments due to the demands of his work, which he poignantly documented in his poetry, particularly regarding the immense strain he experienced while painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Political turmoil in Florence also weighed heavily on him, but perhaps his most notable rivalry was with fellow Florentine artist Leonardo da Vinci, who was over 20 years his senior.

Poetry and Personal Life

Michelangelo’s poetic inclinations, which were initially expressed through his sculptures, paintings, and architectural designs, began to take a literary form in his later years. Although he never married, he formed a deep bond with a pious and noble widow named Vittoria Colonna, who inspired many of his over 300 poems and sonnets. Their friendship provided Michelangelo with considerable solace until Colonna’s passing in 1547, marking a significant loss in his life.

Sculptures

Pietà

In 1498, shortly after Michelangelo’s relocation to Rome, Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas—representing French King Charles VIII—commissioned the sculpture Pietà, depicting Mary cradling the deceased Jesus across her lap.

At just 25 years old, Michelangelo completed the statue in under a year, and it was originally placed in the cardinal’s tomb within the church. Measuring 6 feet in width and nearly the same in height, Pietà has been relocated five times and currently resides in a prominent position at St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

Carved from a single block of Carrara marble, the statue captivates viewers with its intricate depiction of fabric, the positioning of its subjects, and the lifelike quality of the skin. The term Pietà, meaning “pity” or “compassion,” aptly describes the emotional impact it has had on audiences since its unveiling.

Remarkably, Pietà is the only work to bear Michelangelo’s name. Legend suggests he carved his signature into the sash across Mary’s chest after overhearing pilgrims attributing the work to another artist. Today, Pietà remains universally revered as a masterpiece.

David

Between 1501 and 1504, Michelangelo took on the commission for a statue of David, a project previously attempted by two other sculptors but ultimately abandoned. He transformed a 17-foot piece of marble into an imposing representation of the biblical figure.

The statue embodies a compelling juxtaposition of strength and vulnerability, showcasing the sinewy form of David alongside an expression that conveys profound humanity and courage. Originally commissioned for the Florence Cathedral, the Florentine government chose instead to display it at the Palazzo Vecchio. David now resides in the Accademia Gallery in Florence.

Paintings

Sistine Chapel

Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to transition from sculpture to painting, tasking him with the decoration of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling, which he unveiled on October 31, 1512. This monumental project sparked Michelangelo’s creative imagination, leading him to expand the initial plan from 12 apostles to over 300 figures within the sacred space. (Due to an infectious fungus in the plaster, the original work had to be removed and later recreated.)

Michelangelo famously dismissed all his assistants, deeming them unfit, and completed the 65-foot ceiling alone. He dedicated countless hours to the work, lying on his back and meticulously guarding his vision until its completion.

The resulting masterpiece exemplifies the principles of High Renaissance art, interweaving themes of symbology, prophecy, and humanism that Michelangelo absorbed throughout his youth.

Creation of Adam

Among the vibrant scenes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Creation of Adam stands out as the most iconic. This powerful depiction of God extending His hand to touch Adam’s finger has inspired countless artists, including Raphael, who altered his style after witnessing Michelangelo’s work.

Last Judgment

In 1541, Michelangelo unveiled the monumental Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. The immediate public response was one of outrage, with critics deeming the nude figures inappropriate for such a sacred setting, leading to calls for the fresco’s destruction.

In a defiant response, Michelangelo incorporated portrayals of his chief critic as a devil and himself as the flayed St. Bartholomew within the composition.

Architecture

While Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint throughout his career, the physical demands of painting the Sistine Chapel prompted him to focus more intently on architecture. He dedicated the subsequent decades to completing the tomb of Julius II, which had been interrupted for the Pope’s chapel commission, while also designing the Medici Chapel and the Laurentian Library—situated across from the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence. These architectural contributions are regarded as pivotal in the evolution of architectural design.

Michelangelo’s crowning architectural achievement came in 1546 when he was appointed chief architect of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Personal Life

Was Michelangelo Gay?

In 1532, Michelangelo developed a deep attachment to the young nobleman Tommaso dei Cavalieri, dedicating numerous romantic sonnets to him. Scholars, however, debate the nature of their relationship, questioning whether it was platonic or of a homosexual nature.

Death

Michelangelo passed away on February 18, 1564, just weeks shy of his 89th birthday, at his residence in Macel de’Corvi, Rome, following a brief illness. His body was transported back to Florence by his nephew, where he was celebrated as the “father and master of all the arts.” He was interred at the Basilica di Santa Croce, his chosen burial site.

Legacy

Unlike many artists of his time, Michelangelo achieved significant fame and wealth during his lifetime. He uniquely experienced the publication of two biographies about his life, penned by Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi.

Michelangelo’s artistic genius has continued to resonate through the centuries, establishing his name as synonymous with the pinnacle of humanist expression during the Renaissance.