Table of Contents

Who Was Woody Guthrie?

Woody Guthrie was a prolific American folk musician and songwriter, credited with composing over 1,000 songs, including notable works such as “So Long (It’s Been Good to Know Yuh)” and “Union Maid.” His most renowned piece, “This Land Is Your Land,” emerged as an unofficial national anthem, resonating deeply with themes of equality and belonging. After serving in World War II, Guthrie continued to advocate for farmers and workers through his music. His autobiography, Bound for Glory, published in 1943, later inspired a film adaptation in 1976. His legacy further extends to his son, Arlo Guthrie, who also achieved recognition in the music industry.

Early Life

Born on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma, Woody Guthrie was the second son of Charles and Nora Belle Guthrie. He entered the world just weeks after Woodrow Wilson was nominated as the Democratic presidential candidate in 1912. As Guthrie later shared with audiences, “My father was a hard, fist-fighting Woodrow Wilson Democrat, so Woodrow Wilson was my name.” Growing up in a musically inclined family, he was exposed to a diverse range of folk tunes, which he learned to play on both guitar and harmonica.

Tragedy struck early in Guthrie’s life, shaping his worldview and future songwriting. He endured the accidental death of his older sister Clara, a devastating fire that destroyed the family home, his father’s financial collapse, and the institutionalization of his mother due to Huntington’s disease. At the age of 14, Guthrie and his siblings were left to navigate life largely on their own while their father sought work in Texas to settle debts. During this tumultuous period, Guthrie turned to street performances for sustenance, honing his musical abilities while cultivating a profound social conscience that would become integral to his artistry.

At 19, Guthrie married his first wife, Mary Jennings, in Texas. The couple had three children: Gwen, Sue, and Bill. However, the Great Depression severely impacted the Guthrie family, and when the drought-ravaged Great Plains became synonymous with the Dust Bowl, Guthrie left his family in 1935 to join the thousands of “Okies” migrating westward in search of employment. Like many Dust Bowl refugees, he relied on hitchhiking, freight trains, and performing for food, evolving into a musical advocate for labor rights and leftist causes.

These challenging experiences laid the foundation for Guthrie’s songwriting and storytelling, as captured in his autobiography, Bound for Glory. During these years, he developed an enduring love for travel that would define much of his life and career.

Folk Revolutionary

In 1937, Woody Guthrie arrived in California, where he secured a position as a radio performer of traditional folk music alongside his partner, Maxine “Lefty Lou” Crissman, at KFVD in Los Angeles. The duo quickly attracted a devoted following among the disenfranchised “Okies” residing in migrant camps throughout California. It was not long before Guthrie’s populist sentiments began to permeate his songwriting.

By 1940, Guthrie’s restless spirit led him to New York City, where he found a welcoming community of leftist artists, union organizers, and folk musicians. Collaborations with prominent figures such as Alan Lomax, Leadbelly, Pete Seeger, and Will Geer significantly propelled Guthrie’s career. He became a passionate advocate for social causes, helping to establish folk music as both a vehicle for change and a commercially viable genre within the music industry. His work with the Almanac Singers elevated his status in the public eye, earning him considerable acclaim. However, the fame and challenges of life on the road contributed to the dissolution of his marriage in 1943. A year later, he recorded “This Land Is Your Land,” an iconic populist anthem that continues to resonate today and is often regarded as an alternative national anthem.

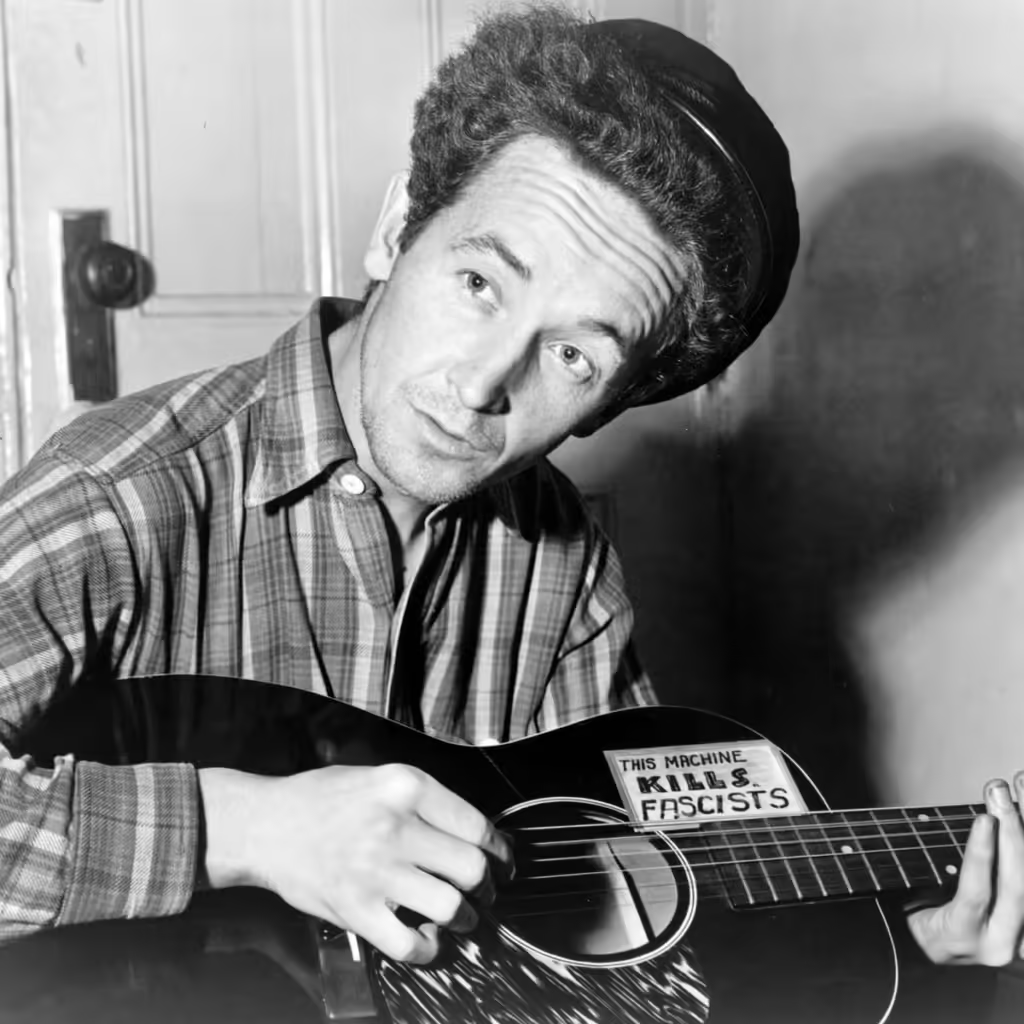

During World War II, Guthrie joined the Merchant Marine, where he began to compose music with a more pronounced antifascist message. He famously performed with the slogan “This Machine Kills Fascists” emblazoned across his acoustic guitar. While on furlough from the Merchant Marine, he married Marjorie Greenblatt Mazia, and after the war, the couple settled in Coney Island, New York, eventually raising four children: Cathy, Arlo, Joady, and Nora. This period marked a prolific chapter in Guthrie’s musical journey, as he continued to produce political anthems alongside beloved children’s songs such as “Don’t You Push Me Down,” “Ship In The Sky,” and “Howdi Doo.”

Later Years and Death

By the late 1940s, Guthrie began exhibiting symptoms of Huntington’s chorea, a rare neurological disease that had claimed his mother’s life. The unpredictable physical and emotional challenges posed by the disease profoundly affected him, prompting him to leave his family and embark on a journey with his protégé, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. He eventually returned to California, where he resided in a compound owned by activist and actor Will Geer, which was home to many performers who had been blacklisted during the Red Scare of the early Cold War years. During this time, he met and married his third wife, Anneke Van Kirk, with whom he had his eighth child, Lorina Lynn.

As Guthrie’s health continued to decline throughout the late 1950s, he was hospitalized until his death in 1967. His marriage to Van Kirk succumbed to the strain of his illness, leading to their eventual divorce. In his final years, Guthrie’s second wife, Marjorie, and their children made regular visits to him in the hospital, as did Bob Dylan, one of Guthrie’s most notable musical heirs. Dylan had moved to New York City to seek out his idol, and over time, Guthrie developed a bond with the young artist, who later remarked, “The songs themselves were really beyond category. They had the infinite sweep of humanity in them.”

Woody Guthrie passed away on October 3, 1967, due to complications from Huntington’s chorea. Despite his folk hero status, he remained remarkably modest, often downplaying his creative contributions. “I like to write about wherever I happen to be,” he once said. “I just happened to be in the Dust Bowl, and because I was there and the dust was there, I thought, well, I’ll write a song about it.” His musical legacy endures, having inspired a generation of folk singers in the 1950s and 1960s who played a pivotal role in driving social change during a tumultuous period in American history.