Table of Contents

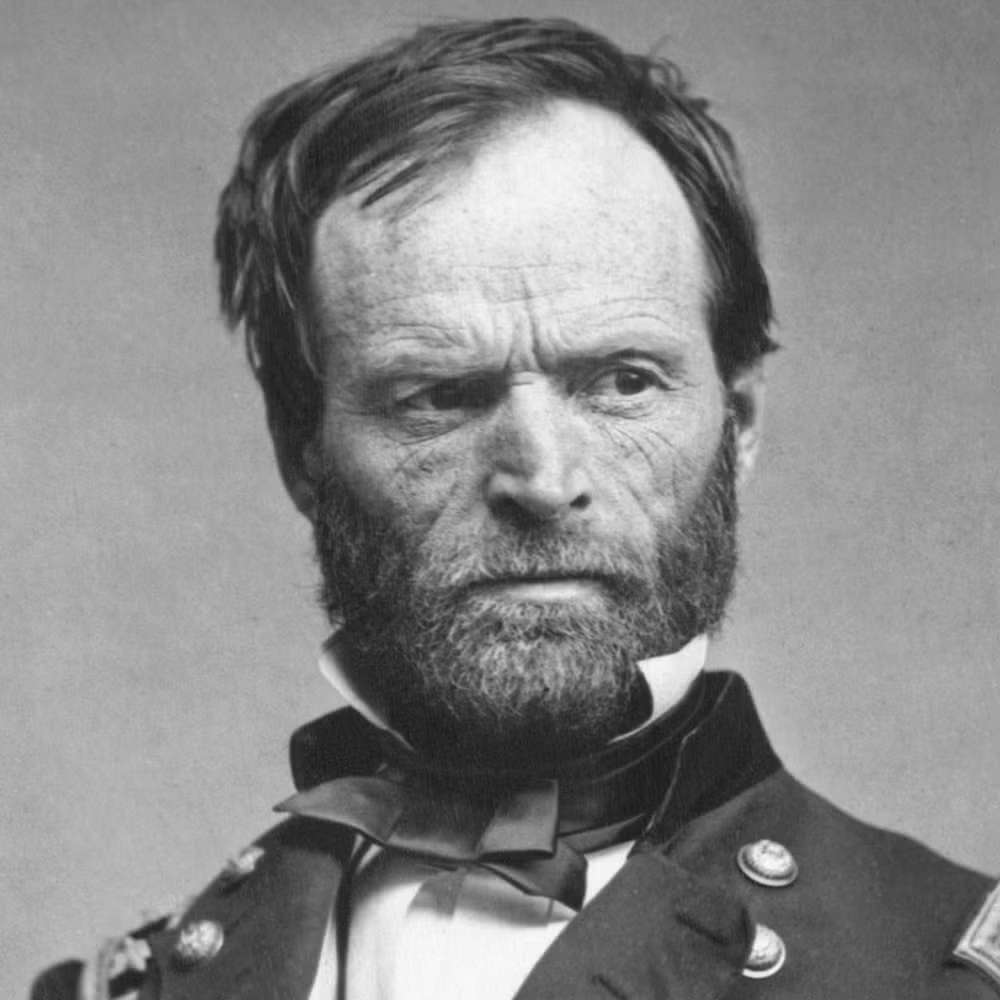

Who Was William Tecumseh Sherman?

William Tecumseh Sherman, a prominent Union general during the American Civil War, is best known for his leadership in the Battle of Shiloh, his infamous March to the Sea, and his role in shaping the modern concept of total warfare. Despite facing early setbacks in his military career, including being temporarily relieved of command, Sherman’s strategic prowess became instrumental in securing Union victory. Often associated with the phrase “war is hell,” Sherman’s aggressive tactics were crucial in devastating the Confederate forces and bringing about the war’s conclusion.

Early Life

Born on February 8, 1820, in Lancaster, Ohio, William Tecumseh Sherman was the sixth of eleven children in a distinguished family. His father, Charles Sherman, was a successful lawyer and an Ohio Supreme Court justice. However, when Sherman was just nine years old, his father passed away unexpectedly, leaving the family financially strained. Sherman was subsequently raised by Thomas Ewing, a close family friend, who was a senator from Ohio and a prominent figure in the Whig Party. Sherman’s middle name, “Tecumseh,” has been the subject of much speculation. In his memoirs, Sherman attributed the name to his father’s admiration for the Shawnee chief of the same name.

Early Military Career

In 1836, with the help of Senator Ewing, Sherman received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Though he excelled academically, Sherman had little regard for the academy’s demerit system, earning numerous minor offenses on his record. He graduated in 1840, ranking sixth in his class. His early military service included assignments in Florida, where he participated in actions against the Seminole Indians, and various posts in Georgia and South Carolina, where he became familiar with the culture and prominent families of the Old South.

Sherman’s early career did not match the glory and fame of many of his contemporaries. Unlike other officers who fought in the Mexican-American War, Sherman spent this period stationed in California, working as an executive officer. In 1850, he married Eleanor Boyle Ewing, the daughter of his benefactor, Thomas Ewing. Despite his promising education and assignments, Sherman grew disillusioned with the U.S. Army, feeling that his prospects were limited. In 1853, he resigned his commission and entered civilian life.

Sherman briefly tried his hand as a banker in California during the gold rush, but his career there was cut short by the Panic of 1857. He then moved to Kansas to practice law, though with little success. In 1859, he became the headmaster of a military academy in Louisiana, where he gained recognition as an effective administrator and became well-liked in the local community. As tensions over slavery and secession escalated in the 1860s, Sherman predicted that a civil war would be long and bloody, with the North ultimately prevailing. When Louisiana seceded from the Union, Sherman resigned his post and moved to St. Louis, seeking to distance himself from the conflict. Despite his personal opposition to slavery, Sherman remained a staunch supporter of the Union. Following the attack on Fort Sumter, Sherman asked his brother, Senator John Sherman, to secure a commission for him in the Union Army.

Service in the Civil War

In May 1861, William Tecumseh Sherman was appointed colonel of the 13th U.S. Infantry and assigned command of a brigade under General William McDowell in Washington, D.C. He participated in the First Battle of Bull Run, where Union forces suffered a significant defeat. Following this, Sherman was dispatched to Kentucky, where his morale and outlook on the war began to deteriorate. He expressed growing pessimism, complaining of logistical shortages and overstating the enemy’s troop strength. His concerns were compounded by a nervous breakdown, leading to a temporary leave of absence. The press, seizing on his troubles, labeled him as “insane.”

Sherman returned to duty in Missouri in mid-December 1861, where he was assigned to rear-echelon commands. He played a pivotal role in supporting Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant during the capture of Fort Donelson in February 1862. The following month, Sherman was assigned to serve under Grant in the Army of West Tennessee, marking the beginning of a significant partnership.

Sherman’s first major test as a combat commander came during the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. Initially dismissing intelligence reports about Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s movements, Sherman failed to take adequate precautions. On April 6, Confederate forces launched a surprise attack, and Sherman, alongside Grant, rallied Union troops to repel the assault by day’s end. With reinforcements arriving overnight, the Union launched a counteroffensive on the morning of April 7, forcing the Confederates to retreat. This battle cemented Sherman’s bond with Grant, leading to a lifelong professional relationship.

Sherman remained in the West, continuing to serve alongside Grant in the campaign against Vicksburg. Despite the mounting pressure from the press, which criticized both men relentlessly, Sherman’s strategic capabilities became evident. As one newspaper lamented, the “Army was being ruined in mud-turtle expeditions, under the leadership of a drunkard [Grant] whose confidential adviser [Sherman] was a lunatic.” Ultimately, Vicksburg fell, and Sherman was given command of three Union armies in the West.

Evolving Toward “Total War”

In February 1864, Sherman initiated a campaign from Vicksburg aimed at destroying the railroad hub at Meridian, Mississippi, which was strategically located at the intersection of three major rail lines. Recognizing the urgency of the mission, Sherman’s forces cut supply lines and lived off the land as they advanced. Confederate resistance, led by General Leonidas Polk, was ineffective against Sherman’s 45,000-strong army. On February 11, 1864, Sherman’s troops attacked Meridian, destroying vital railroad infrastructure and scattering Confederate forces. This campaign set the stage for Sherman’s more notorious “March to the Sea.”

In September 1864, Confederate forces under General John Bell Hood were forced to evacuate Atlanta after a prolonged siege. As they withdrew, Hood’s forces destroyed supplies and munitions, but Sherman’s forces ultimately seized the city. Sherman ordered the city to be burned, further demoralizing the South. He then embarked on his famous March to the Sea, a campaign of total destruction that left a 60-mile-wide swath of devastation across Georgia. This military strategy, later dubbed “total war,” aimed to break the South’s will to fight by destroying both its infrastructure and its capacity to resist.

Post-War Life and Death

Following the Civil War, Sherman was appointed general of the U.S. Army by President Grant in 1869. In this role, Sherman was tasked with overseeing the protection of railroad construction from Native American raids. He took a harsh stance toward Native American resistance, ordering the destruction of hostile tribes, while also criticizing government officials who mistreated Native Americans on reservations.

Sherman retired from the Army in February 1884 and lived in St. Louis before relocating to New York City in 1886. There, he pursued interests in theater, painting, and public speaking. Despite offers to run for president, Sherman famously declined, stating, “I will not accept if nominated, and will not serve if elected.”

William Tecumseh Sherman passed away on February 14, 1891, in New York City. His funeral was marked by national mourning, with flags flown at half-staff. Although vilified in the South for his harsh tactics, Sherman is widely regarded by historians as a brilliant military strategist and tactician. His concept of “total war” fundamentally changed the nature of warfare, with Sherman himself acknowledging its brutal reality: “War is hell.”