Table of Contents

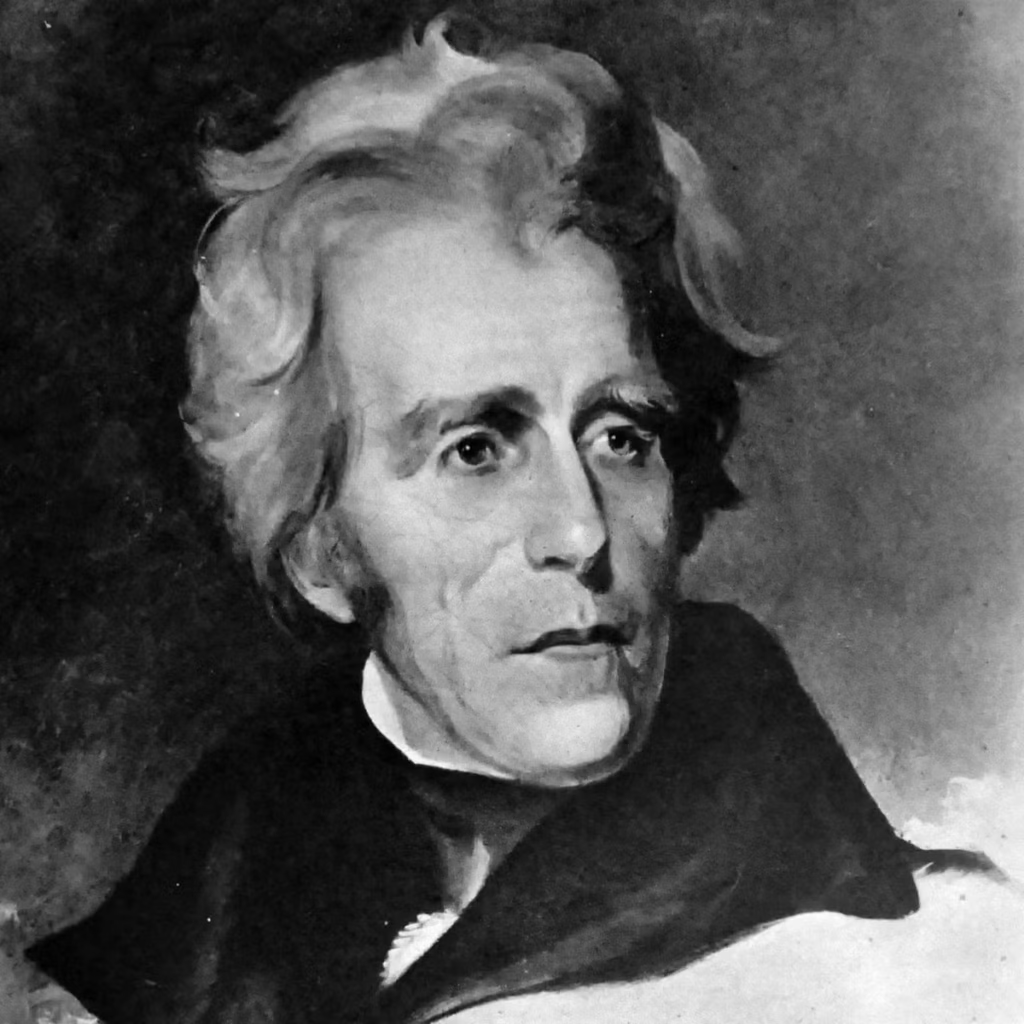

Who Was Andrew Jackson?

Andrew Jackson was a prominent American figure, renowned as a lawyer, landowner, and military leader. Born on March 15, 1767, Jackson rose to national prominence after his decisive victory over the British at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. His military success propelled him to political office, and in 1828, he was elected as the seventh president of the United States. Often referred to as the “people’s president,” Jackson was known for his populist appeal, his role in founding the Democratic Party, and his controversial policies, including the destruction of the Second Bank of the United States and the forced relocation of Native American tribes. Jackson died on June 8, 1845.

Early Life

Born to Scots-Irish immigrants Andrew and Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, Andrew Jackson grew up in poverty in the backwoods of the Waxhaws region, an area straddling the border of North and South Carolina. The exact location of his birth remains uncertain due to the lack of a defined border at the time. His father died unexpectedly just weeks before his birth, leaving the family in difficult circumstances. Jackson’s early education was sporadic, and he faced numerous hardships as the Revolutionary War unfolded in the Carolinas.

At the age of 13, Jackson joined a local militia and served as a courier for the patriot cause. In 1781, he and his brother Robert were captured by British forces, and during their imprisonment, Jackson was marked by a brutal encounter with a British officer who slashed his face and hand with a sword. Both brothers contracted smallpox while in captivity, and Robert ultimately died from the disease.

Orphaned at Age 14

Just after the British released Jackson and his brother in a prisoner exchange, tragedy struck again. Robert passed away, and shortly thereafter, Jackson’s mother, who had been nursing soldiers injured during the war, died of cholera. At the age of 14, Jackson was orphaned, an experience that profoundly shaped his character and fueled a lifelong resentment toward the British.

Raised by relatives, Jackson pursued a legal career in Salisbury, North Carolina, in his late teens. He passed the bar exam in 1787 and quickly built a successful law practice. By 1796, Jackson had moved to Nashville, where he expanded his wealth through land acquisitions. That same year, he played a key role in drafting the Tennessee Constitution and was elected as Tennessee’s first representative to the U.S. House of Representatives. Although he briefly served in the Senate, Jackson resigned after only eight months. In 1798, he was appointed as a circuit judge on the Tennessee superior court, a role he held until 1804.

Military Career and the War of 1812

Although Andrew Jackson lacked formal military experience, he was appointed major general of the Tennessee militia in 1802. During the War of 1812, he commanded U.S. troops in a decisive five-month campaign against the Creek Nation, which had aligned with the British. This conflict followed the massacre of hundreds of settlers at Fort Mims (modern-day Alabama) by Creek forces. Jackson’s leadership culminated in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, where his forces defeated approximately 800 Creek warriors. This victory not only secured Jackson’s reputation but also resulted in the acquisition of 20 million acres of land in present-day Georgia and Alabama. In recognition of his success, the U.S. military promoted him to major general.

Jackson’s military endeavors continued without specific orders when, in 1814, he led his forces into Spanish Florida, capturing the strategic outpost of Pensacola. Afterward, he pursued British forces to New Orleans. The Battle of New Orleans, fought on January 8, 1815, marked the final engagement of the War of 1812. Despite being outnumbered nearly two-to-one, Jackson’s forces achieved a decisive victory, cementing his status as a national hero.

The Nickname “Old Hickory”

Jackson’s success in battle earned him widespread acclaim, including the gratitude of Congress and a gold medal. His soldiers, who admired his toughness and resilience, likened him to “old hickory wood,” an enduring symbol of strength. As a result, Jackson became affectionately known as “Old Hickory.”

The First Seminole War and the Adams-Onís Treaty

In 1817, Jackson was called upon to lead military action during the First Seminole War. Exceeding his orders, he invaded Spanish Florida, capturing St. Mark’s and Pensacola, executing two British nationals who had assisted Native American forces, and toppling the government of West Florida. His actions provoked a strong diplomatic response from Spain, and there were calls for his censure in Congress. However, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams defended Jackson, arguing that his actions were in the national interest. The controversy ultimately led to the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty, through which Spain ceded Florida to the United States. Jackson subsequently served as the military governor of Florida from 1821.

Senator and Presidential Aspirations

Jackson’s military victories significantly enhanced his political stature. In 1822, the Tennessee legislature nominated him for the U.S. presidency, and he was elected to the U.S. Senate the following year. By 1824, Jackson’s popularity soared, and he was nominated for president by a Pennsylvania convention. Though he won the popular vote, no candidate secured a majority in the Electoral College, resulting in the election being decided by the House of Representatives. Speaker of the House Henry Clay, who had finished fourth in the Electoral College, threw his support behind John Quincy Adams, who ultimately won the presidency. Jackson’s supporters decried this outcome as a “Corrupt Bargain” after Adams appointed Clay as his secretary of state, which further fueled Jackson’s political ambitions.

Presidency

In the presidential election of 1828, Jackson, with South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun as his vice-presidential running mate, defeated Adams in a landslide. Jackson’s victory marked the emergence of the first frontier president, as he was the first chief executive not from Massachusetts or Virginia.

Jackson’s inauguration was marked by unprecedented public participation, as he invited ordinary citizens to attend the White House ball. The event drew an overwhelming crowd, causing chaos and property damage. Jackson’s response to the unruly crowd earned him the nickname “King Mob,” reflecting both his populist appeal and the tumultuous nature of his presidency.

Accomplishments of Andrew Jackson

Founding of a New Political Party

In the wake of the contentious 1824 presidential election, where Jackson’s defeat sparked widespread dissatisfaction, he was re-nominated for the presidency in 1825, three years before the next election. This period also marked a significant schism within the Democratic-Republican Party, ultimately leading to its division. Jackson’s supporters, who rallied behind the populist figure of “Old Hickory,” identified themselves as Democrats, laying the foundation for the future Democratic Party. Ironically, Jackson’s political opponents coined the nickname “jackass” to ridicule him, a label which Jackson embraced and transformed into a symbol. The donkey would become an enduring emblem of the Democratic Party.

Exercising Veto Power

Once in office, Jackson asserted his authority over legislative matters, breaking away from the traditional use of presidential veto power. Unlike his predecessors, who exercised veto power based primarily on constitutional concerns, Jackson expanded its use to include policy disagreements, setting a new precedent for future presidents. He also advocated for direct popular participation in the electoral process, pushing for the abolition of the Electoral College, a move that earned him the title of “the people’s president.” Additionally, Jackson implemented the “spoils system,” replacing many federal officeholders with loyal supporters, a controversial approach that would influence U.S. politics for years to come.

Opposition to the Second Bank of the United States

One of Jackson’s most defining actions as president was his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States. A nominally private institution, the bank was seen by Jackson as a corrupt, elitist entity that exerted undue control over the nation’s economy. The bank’s influence and its manipulation of paper currency drew Jackson’s ire. His principal opponent, Henry Clay, sought to recharter the bank during the 1832 election, believing it to be essential for economic stability. Jackson vetoed the re-charter, arguing that it advanced the interests of the few at the expense of the many. The president’s stance resonated with the public, and he triumphed in the 1832 election, securing over 56% of the popular vote. By the end of Jackson’s second term, the Second Bank was effectively shut down.

Conflict with Vice President John C. Calhoun

Jackson’s political challenges also extended to his vice president, John C. Calhoun, particularly over the issue of federal tariffs. In 1828 and 1832, tariffs were passed that Southern leaders, particularly in South Carolina, argued disproportionately benefited Northern manufacturers. In response, South Carolina issued a resolution declaring the tariffs null and void within the state, even threatening secession. Calhoun, a proponent of states’ rights, supported this stance. In defense of federal authority, Jackson threatened military action to enforce the laws. The conflict escalated to the point where Calhoun resigned as vice president in December 1832, becoming the first vice president in U.S. history to do so. The crisis was ultimately resolved with a compromise tariff and a provision granting the president the power to use force if necessary to uphold federal laws, though the debate over states’ rights foreshadowed the Civil War.

First Assassination Attempt

During Jackson’s second term, he survived the first assassination attempt on a sitting U.S. president. On January 30, 1835, as Jackson left a memorial service in the U.S. Capitol, he was confronted by Richard Lawrence, a mentally unstable house painter who believed himself to be the rightful heir to the British throne. Lawrence attempted to shoot Jackson with a gold-plated pistol, but the weapon misfired. He then drew a second pistol, which also failed to discharge. Jackson, undeterred, charged at Lawrence and struck him with his cane until bystanders intervened. Lawrence was later deemed insane and was committed to psychiatric care for the remainder of his life.

Controversial Decisions

Trail of Tears

Despite his widespread popularity and success, Andrew Jackson’s presidency was marked by significant controversy, particularly in his dealings with Native American tribes. A key component of his administration’s policies was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which granted Jackson the authority to negotiate treaties that resulted in the forced relocation of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands to areas west of the Mississippi River.

One of the most egregious actions taken by Jackson was his failure to enforce a Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Cherokee Nation. Despite the Court’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia, which asserted that Georgia had no legal claim over Cherokee lands, Jackson refused to intervene. This refusal led to the displacement of the Cherokee people and the infamous Trail of Tears, during which approximately 15,000 Cherokees were forcibly relocated to present-day Oklahoma. This tragic event caused the deaths of around 4,000 individuals due to exposure, disease, and starvation.

Dred Scott Decision

In another controversial chapter of Jackson’s legacy, he nominated his ally Roger Taney to the U.S. Supreme Court. While initially rejected in 1835, Taney was re-nominated and confirmed as Chief Justice in 1836. Taney’s most notorious ruling was in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, which declared that African Americans were not citizens and therefore had no right to sue in federal court. Furthermore, the decision asserted that Congress lacked the authority to prohibit slavery in U.S. territories. Taney’s decision played a significant role in exacerbating tensions leading up to the Civil War.

In response to Jackson’s presidency, his political opponents formed the Whig Party during his second term. The Whigs, who opposed Jackson’s strong-handed approach, coined the nickname “King Andrew I” to describe what they saw as his autocratic rule. While the Whigs failed to win the 1836 presidential election, they successfully captured the presidency in 1840.

Jackson’s legacy also includes his handling of the economy. His staunch opposition to paper money, which he believed favored speculators and harmed the common man, led to the issuance of the Specie Circular in 1836. This policy, which required land payments to be made in gold or silver, resulted in the collapse of numerous banks and contributed to the Panic of 1837, which devastated the economy during the presidency of his successor, Martin Van Buren.

Andrew Jackson’s Personal Life

Rachel Jackson

Andrew Jackson’s personal life was also a source of controversy, particularly concerning his wife, Rachel Donelson Robards. When Jackson married Rachel in 1791, her divorce from her first husband, Captain Lewis Robards, had not been finalized, leading to accusations of bigamy. Although the couple legally remarried in 1794, the issue was used against Jackson during his 1828 presidential campaign.

Andrew Jackson’s Duels

Known for his fiery temper, Jackson’s reputation for quarreling became infamous. He famously participated in a duel in 1806 with Charles Dickinson, who had insulted Jackson’s wife. Despite being shot in the chest, Jackson stood his ground and fatally wounded Dickinson. Jackson carried the bullet from this duel, along with one from a subsequent encounter, for the rest of his life.

The Jacksons had no biological children but adopted three sons, including two Native American orphans found during the Creek War. Tragically, one of the children, Theodore, died shortly after being adopted, and Lyncoya, another adopted son, died young as well. The Jacksons also adopted Andrew Jackson Jr., the son of Rachel’s brother.

Death of Rachel Jackson

Rachel Jackson died of a heart attack on December 22, 1828, just months before Jackson’s inauguration. Jackson, devastated by her passing, believed the stress of the vitriolic campaign had contributed to her death. Rachel was buried two days later, on Christmas Eve.

Andrew Jackson’s Death

Jackson lived until June 8, 1845, when he died at the age of 78. The cause of death was later determined to be lead poisoning from the bullets lodged in his chest. He was buried next to his beloved wife Rachel at The Hermitage, his plantation in Tennessee.

Legacy

The Hermitage

Jackson’s home, The Hermitage, located in Davidson County, Tennessee, was an expansive cotton plantation. Jackson acquired the property in 1798, and by the time of his death in 1845, it had grown to encompass approximately 150 enslaved people. The plantation remains a testament to Jackson’s complex legacy, with both his political contributions and his involvement in the system of slavery.

Jackson and Donald Trump

In recent years, Andrew Jackson has been recognized as an influential predecessor by some U.S. presidents, including Donald Trump, who displayed a portrait of Jackson in the White House. The portrait was prominently featured behind Trump during a 2017 event honoring the Navajo Code Talkers, Native Americans who played a key role in World War II communications. This moment drew attention to the irony of Jackson’s legacy, given his policies toward Native Americans.

Jackson’s presidency remains one of the most contentious and polarizing in American history, a period marked by significant political and social change, as well as profound injustice. His advocacy for the “common man” reshaped the nation, yet his actions toward Native Americans and African Americans continue to provoke debate about his legacy.