Table of Contents

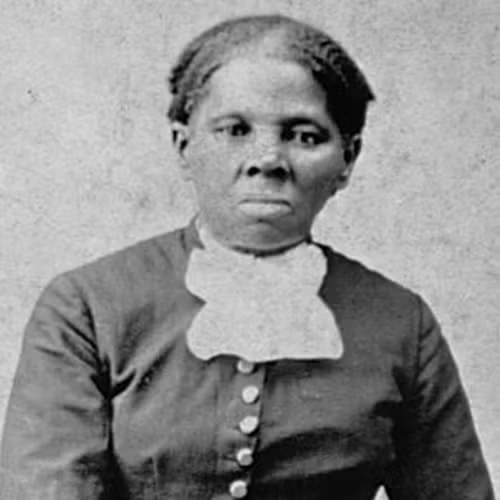

Who Was Harriet Tubman?

Harriet Tubman, born into slavery in Maryland, escaped to freedom in the North in 1849 and became one of the most renowned “conductors” of the Underground Railroad. Tubman risked her life countless times to guide dozens of family members and other enslaved people from the oppression of the plantation system to safety along this covert network of escape routes and safe houses. Before the American Civil War, Tubman was an influential abolitionist, and during the war, she served the Union Army in various capacities, including as a spy. After the war, Tubman dedicated herself to helping formerly enslaved people and the elderly, working tirelessly to improve their lives. In recognition of her profound impact on American history, the U.S. Treasury Department announced in 2016 that Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the center of a newly designed $20 bill.

Early Life and Family

Harriet Tubman’s exact birth date is unknown, though it is believed she was born between 1820 and 1825, with recent research and oral history suggesting an early 1822 birthdate. She was one of nine children born to enslaved parents in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her mother, Harriet “Rit” Green, was owned by Mary Pattison Brodess, and her father, Ben Ross, was owned by Anthony Thompson, who later married Brodess.

Tubman was originally named Araminta Harriet Ross, and her family affectionately called her “Minty.” She later changed her name to Harriet, likely in honor of her mother, around the time of her marriage.

Tubman’s early years were marked by profound hardship. The Brodess family’s son, Edward, sold three of Tubman’s sisters to faraway plantations, which tore her family apart. When a Georgia trader approached Mary Brodess about purchasing Rit’s youngest son, Moses, Rit resisted, refusing to let her family be further divided—a powerful act of defiance that would influence young Harriet deeply.

Violence and cruelty were constant elements of Tubman’s early life. She endured physical punishment regularly, including one particularly harrowing incident in which she was lashed five times before breakfast. The scars from this abuse stayed with her for the rest of her life.

The most severe injury Tubman endured occurred when she was a teenager. Sent to a dry goods store for supplies, Tubman encountered a slave who had left the fields without permission. When the overseer demanded her help in restraining the runaway, Tubman refused. In retaliation, the overseer hurled a two-pound weight at her, striking her in the head. This injury caused her to experience lifelong seizures, severe headaches, and narcoleptic episodes. She also began to experience vivid dream states, which she interpreted as religious visions.

Though Tubman’s father, Ben, was freed from slavery at age 45 according to the terms of a previous owner’s will, he remained economically bound to the same people who had enslaved him. Ben’s freedom offered him little opportunity, and he continued to work as a timber estimator for his former owners. Despite the manumission clauses for Rit and her children, the family remained enslaved, and Ben had no means to challenge the decision of his former owners, highlighting the complicated nature of freedom and bondage in that era.

Harriet Tubman: A Legacy of Courage and Freedom

Harriet Tubman’s journey to freedom began in 1849, when she escaped from slavery in Maryland using the Underground Railroad, an extensive network of safe houses and routes that helped fugitive slaves reach free states or Canada. Tubman’s decision to flee was spurred by a combination of illness and the death of her owner. Fearing further separation from her family and concerned for her own survival as a sickly, low-value slave, she set her sights on Philadelphia.

Accompanied by her two brothers, Ben and Harry, Tubman began her escape on September 17, 1849. However, a public notice offering a reward for her return caused her brothers to reconsider, and they returned to the plantation. Determined to secure her own freedom, Tubman continued alone, traveling nearly 90 miles to the free state of Pennsylvania. Upon crossing the border, she was overwhelmed with emotion, recalling later, “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person… there was such a glory over everything.”

Underground Railroad Conductor

Rather than staying in the relative safety of the North, Tubman made it her mission to rescue family members and others still enslaved in the South. Over the course of 13 trips, she guided dozens of fugitives to freedom, earning the title of “conductor” for her efforts. In December 1850, after learning that her niece and her children were about to be sold, Tubman successfully led them to Philadelphia. This was just the first of many missions.

The passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed escaped slaves to be captured in the North and returned to slavery, made Tubman’s work even more dangerous. In response, she rerouted the Underground Railroad to Canada, a place where slavery was prohibited. In December 1851, Tubman led a group of 11 fugitives northward, possibly stopping at the home of abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Tubman’s influence expanded beyond the Underground Railroad. In April 1858, she met abolitionist John Brown, who advocated for violent resistance against slavery. Tubman, who shared his radical goals, helped recruit for Brown’s ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry, and after his execution, praised him as a martyr.

Civil War Contributions

During the Civil War, Tubman worked for the Union Army as a cook and nurse, eventually becoming an armed scout and spy. She led the Combahee River Raid in 1863, which liberated more than 700 slaves in South Carolina, making her the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war.

How Many Slaves Did Harriet Tubman Free?

While an 1868 biography exaggerated Tubman’s impact, claiming she had led as many as 300 slaves to freedom, Tubman herself reported rescuing around 70 people during 13 trips. She carried a pistol for protection against slave catchers and used it to reassure runaway slaves, encouraging them to keep going.

Personal Life and Family

In 1844, Harriet Tubman married John Tubman, a free Black man. Little is known about their marriage, and it is unclear whether they lived together after her escape. In 1869, Tubman married Civil War veteran Nelson Davis, and the couple adopted a daughter, Gertie, in 1874.

Later Years and Death

In 1859, Tubman purchased land in Auburn, New York, with the help of abolitionist William H. Seward. Despite her fame, she struggled financially, relying on the support of friends and admirers, including the proceeds from her 1868 biography, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. In 1903, she donated a parcel of land to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, which was later used to establish the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged in 1908.

Tubman died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913, at the age of approximately 93. She was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn.

Harriet Tubman’s Lasting Impact

Harriet Tubman’s legacy has endured for generations. She was celebrated as one of the most influential Americans of her time and continues to inspire civil rights movements today. In 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department announced that Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill, a decision that was widely praised for honoring her legacy of fighting for freedom and equality.

Tubman in Popular Culture

Tubman’s life has been the subject of numerous adaptations, including the 1978 miniseries A Woman Called Moses, which starred Cicely Tyson, and the 2019 film Harriet, in which Cynthia Erivo portrayed Tubman. Erivo’s performance earned her several prestigious nominations, including for an Academy Award.

Harriet Tubman’s life remains a testament to bravery, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to justice. Her efforts not only freed hundreds from slavery but also paved the way for future generations to fight for equality and human rights.