Table of Contents

Who Was Squanto?

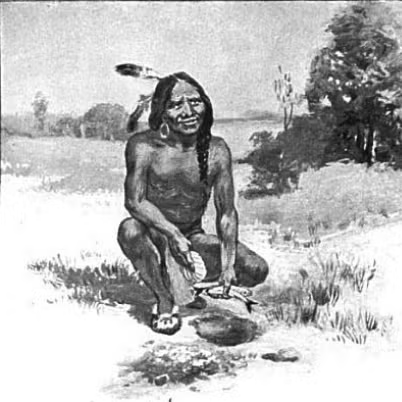

Squanto, also known as Tisquantum, was a Native American of the Patuxet tribe, born around 1580 near present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts. His early life remains largely undocumented. In 1614, he was abducted by English explorer Thomas Hunt, who took him to Spain and sold him into slavery. Squanto managed to escape, making his way back to North America by 1619. Upon his return, he discovered that his tribe had been decimated by disease. Squanto later became instrumental to the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth, serving as an interpreter, guide, and advisor during the early 1620s. He passed away in November 1622 in Chatham, Massachusetts.

Early Life and Capture

Born around 1580 near present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, Squanto—also known as Tisquantum—played a pivotal role as an interpreter and guide for the Pilgrim settlers in the 1620s. Despite his significance in early American history, details about Squanto’s early life remain sparse. A member of the Patuxet tribe, he was captured in 1605 along the Maine coast by Captain George Weymouth, who was on an expedition commissioned by Sir Ferdinando Gorges of the Plymouth Company. Weymouth took Squanto and several other Native Americans to England, likely believing that displaying the captives would interest his financial backers. In England, Squanto lived with Gorges, who taught him English and later employed him as an interpreter and guide.

Interpreter and Guide for the Pilgrims

Fluent in English, Squanto returned to his homeland in 1614 with English explorer John Smith, possibly serving as a guide. However, he was soon captured by another British explorer, Thomas Hunt, and sold into slavery in Spain. After escaping slavery, Squanto lived with monks for several years before finally returning to North America in 1619. Tragically, upon his return, he discovered that his entire Patuxet tribe had perished due to a smallpox epidemic. With no tribe to return to, Squanto joined the neighboring Wampanoag people.

In 1621, Squanto was introduced to the Pilgrims at Plymouth and played a crucial role as an interpreter between the Pilgrims and Wampanoag Chief Massasoit. His language skills and knowledge of both Native American and English customs made him invaluable in facilitating communication and building relationships. Later that year, he helped organize and participate in the first Thanksgiving celebration, following a successful harvest by both the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags. Squanto’s relationship with the Pilgrims deepened further when he helped them find a lost boy and offered practical assistance with agriculture and fishing.

Squanto’s unique position and knowledge of English customs afforded him considerable influence. He sought to elevate his status among other Native American groups by exaggerating his authority with the colonists. At one point, he claimed that he could control the English and even threatened to unleash a plague, which he falsely asserted was being held in English storage pits, should his demands not be met.

Death

Squanto, deeply entangled in the complex politics between the settlers and the local Indigenous tribes, passed away in November 1622, near Chatham, Massachusetts. While serving as a guide for Governor William Bradford, he succumbed to a fever, marking the end of his remarkable yet tumultuous life.