Table of Contents

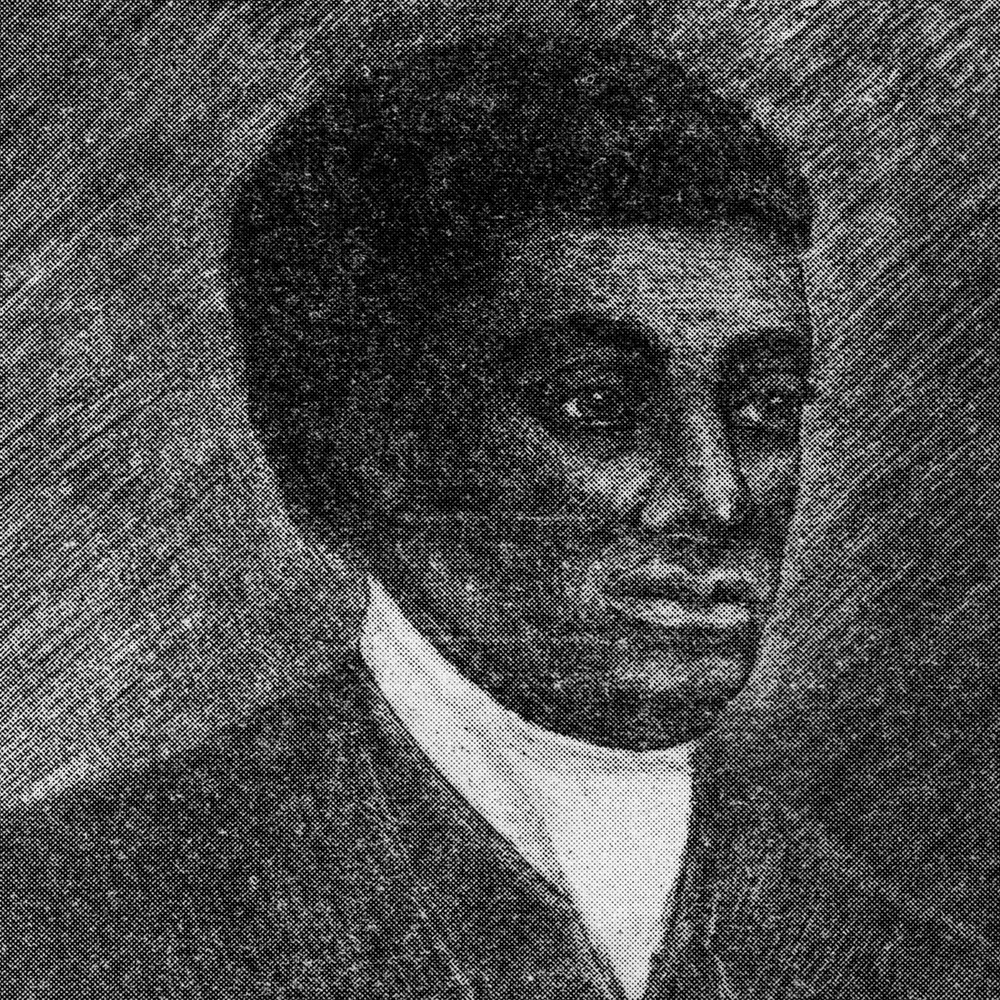

Who Was Benjamin Banneker?

Benjamin Banneker was a prominent free Black man and landowner in the vicinity of Baltimore, Maryland. He was largely self-educated in the fields of astronomy and mathematics, demonstrating remarkable intellectual prowess for his time. In the 1790s, Banneker utilized his knowledge to produce a series of influential almanacs that contained astronomical calculations and weather predictions.

In addition to his contributions to science, Banneker played a vital role in the surveying of the territory designated for the construction of the United States capital, Washington, D.C. His advocacy for civil rights was evident through his correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, in which he politely urged the then-Secretary of State to take action toward achieving racial equality. Banneker passed away in October 1806 at the age of 74, leaving behind a legacy of intellect and advocacy for justice.

Early Life and Education

Benjamin Banneker was born on November 9, 1731, in Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland, now recognized as Ellicott City. He was the son of Robert Banneky, an ex-slave, and Mary Banneky, whose lineage included an Englishwoman named Molly Welsh, a former indentured servant, and Bannka, an ex-slave who claimed descent from tribal royalty in West Africa. Because both of his parents were free, Banneker was fortunate to escape the constraints of slavery.

His early education was facilitated by his maternal grandmother, who taught him to read. He briefly attended a small Quaker school but primarily relied on self-directed study. Banneker developed a keen interest in astronomy, successfully forecasting lunar and solar eclipses. One of his notable early achievements was the construction of an irrigation system for the family farm. Following his father’s death, Banneker managed his own farm for several years, focusing on the cultivation of tobacco and establishing a successful business based on his crops.

Accomplishments of Benjamin Banneker

Banneker’s Clock

In 1753, Benjamin Banneker was inspired to construct his own clock after receiving a watch from an acquaintance. His curiosity led him to deconstruct the watch, allowing him to study its intricate components and mechanisms. After meticulously documenting his observations, Banneker crafted larger wooden replicas of the components, ultimately resulting in a clock that maintained remarkable accuracy for over 50 years. This achievement garnered him a reputation as a skilled horologist, and he became a sought-after expert for repairing watches, clocks, and sundials. In recognition of his contributions, the Banneker Inc. watch and clock company was named in honor of this 18th-century intellectual.

Washington D.C. Land Survey

Banneker’s remarkable talents caught the attention of the Ellicott family, prominent entrepreneurs known for their successful gristmills in the Baltimore area during the 1770s. George Ellicott, who possessed a substantial personal library, generously loaned Banneker numerous books on astronomy and various other subjects. Utilizing mathematical calculations from these studies, Banneker accurately predicted his first solar eclipse. In 1791, he was hired by Andrew Ellicott, George’s cousin, to assist in the surveying of land for the nation’s capital, which later became Washington, D.C. Banneker primarily operated from an observatory tent, employing a zenith sector to record celestial movements. According to the White House Historical Association, both President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson were aware of Banneker’s vital role in this survey; however, due to an unexpected illness, he was only able to work alongside Ellicott for approximately three months.

Almanacs

Banneker’s most significant legacy lies in the almanacs he published over six consecutive years, from 1792 to 1797. These comprehensive handbooks featured his original astronomical calculations and encompassed a variety of content, including opinion pieces, literary works, and practical information related to medicine and tides, which proved particularly beneficial to fishermen. Beyond the almanacs, Banneker also shared insights on apiculture and meticulously calculated the life cycle of the 17-year locust, further solidifying his status as a multifaceted intellectual.

Letter to Thomas Jefferson

Dear Mr. Jefferson,

In the realm of civil rights, Benjamin Banneker’s contributions were notable, particularly in his efforts to challenge societal prejudices. As a respected figure in the 18th century, Banneker reached out to you in 1791, a time when you were serving as Secretary of State. Despite your status as a slaveholder, Banneker viewed you as someone who might appreciate the humanity of African Americans beyond the confines of slavery. With this belief, he composed a letter expressing his hope that you would “readily embrace every opportunity to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and opinions which so generally prevail with respect to us.”

To bolster his argument, Banneker included a handwritten manuscript of an almanac for 1792, showcasing his remarkable astronomical calculations. In his correspondence, he openly acknowledged his identity as “of the African race” and a free man, understanding the audacity of his action in writing to you, especially considering “the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.” He respectfully challenged you and other patriots on the hypocrisy of seeking liberty while perpetuating the enslavement of individuals like himself.

Your response to Banneker was prompt and appreciative. You expressed gratitude for his letter and the accompanying almanac, stating your desire to witness proof of the talents possessed by Black individuals. You asserted that any perceived deficiency in abilities was a consequence of the oppressive conditions faced by people of African descent, both in Africa and America. Furthermore, you conveyed your aspiration for a system to improve their circumstances, emphasizing the importance of addressing the impediments to their progress.

You mentioned taking “the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet, Secretary of the Academy of Sciences at Paris,” viewing it as a crucial document for the justification of your entire race against prevailing doubts. Your letter concluded with a tone of respect, affirming your esteem for Banneker as “Your most obedient humble servant.”

Banneker later published your correspondence alongside his original letter in his 1793 almanac, a testament to his commitment to advocating for civil rights. His bold stance on the issue of slavery garnered significant support from abolitionist societies in Maryland and Pennsylvania, which assisted him in disseminating his almanac.

The exchange between Banneker and Jefferson not only reflects the complexities of the era’s attitudes towards race and slavery but also underscores the enduring impact of Banneker’s efforts in the fight for equality.

Sincerely,

[Your Name]

[Your Title/Position]

[Your Institution or Organization]

[Date]

Later Years

Throughout his life, Benjamin Banneker remained unmarried and childless, dedicating himself to his scientific pursuits. By 1797, however, the sales of his almanac began to decline, prompting him to cease its publication. In the years that followed, he was compelled to sell much of his farm to the Ellicotts and others to sustain his livelihood, continuing to reside in his modest log cabin.

Death

On October 9, 1806, Banneker passed away in his sleep after his customary morning walk, just a month shy of his 75th birthday. In accordance with his wishes, his nephew returned all items that had been loaned from his neighbor, George Ellicott, including Banneker’s invaluable astronomical journal, which serves as one of the few existing records of his life.

He was interred in the family burial ground, located just a few yards from his home, on October 11. During the funeral services, attendees were shocked to witness a fire engulfing his house, which rapidly consumed nearly all of its contents, including his personal belongings, furniture, and his renowned wooden clock. The cause of the blaze was never determined.

Legacy

Banneker’s life was commemorated in an obituary published in the Federal Gazette of Philadelphia, and his contributions have been revisited in literature over the past two centuries. However, the limited materials preserved from his life and career have led to the proliferation of myths and inaccuracies surrounding his legacy.

In 1972, scholar Sylvio A. Bedini published a notable biography titled The Life of Benjamin Banneker: The First African-American Man of Science, which saw a revised edition released in 1999. Additionally, Banneker was depicted in the 1979 docudrama The Man Who Loved the Stars, featuring Ossie Davis in the titular role.

In recognition of his achievements, the U.S. Postal Service honored Banneker with a 15-cent stamp in 1980, as part of its Black Heritage Series, which began in 1978 and continued until 2017. This series celebrates the significant contributions of Black Americans to U.S. history. The stamp features Banneker using a surveying device, with his portrait prominently displayed in the background.

Numerous educational institutions bear Banneker’s name, including Benjamin Banneker Academic High School in Washington, D.C.; Benjamin Banneker Academy for Community Development in Brooklyn, New York; and Benjamin Banneker High School in College Park, Georgia.

Moreover, the Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum in Catonsville, Maryland, features a replica of his log cabin and highlights his life story. Additionally, the Banneker-Douglas Museum in Annapolis serves as Maryland’s official museum dedicated to African American heritage.