Table of Contents

Who Was Albert Einstein?

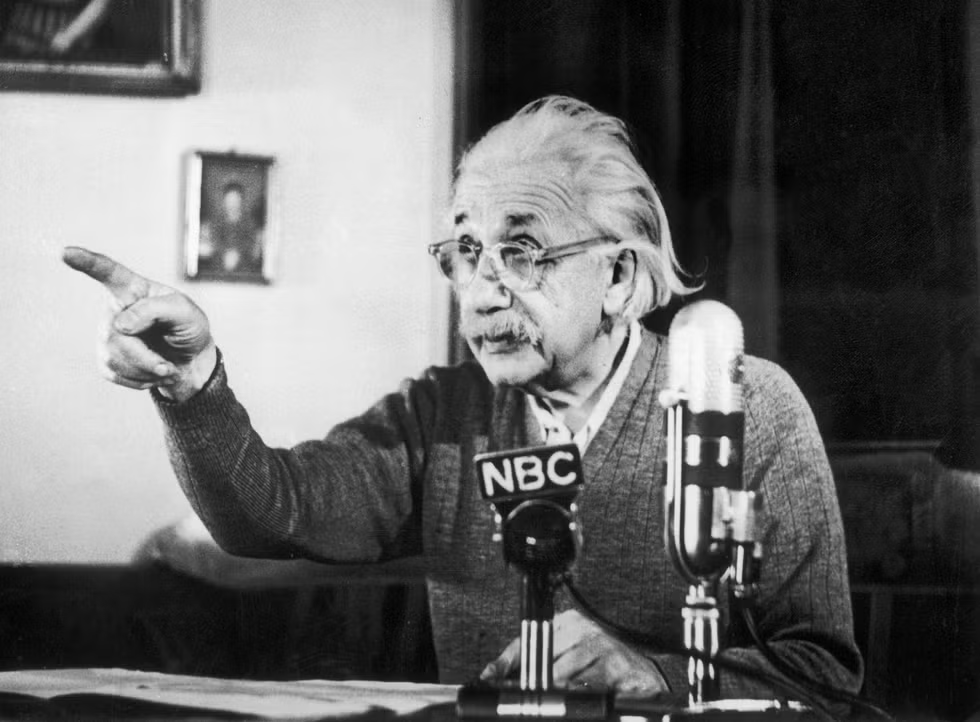

Albert Einstein was a renowned German mathematician and physicist, celebrated for formulating the special and general theories of relativity, which fundamentally transformed the understanding of space, time, and gravity. In recognition of his groundbreaking work, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, a pivotal contribution to quantum theory.

In the early 1930s, as a result of increasing hostility from the German Nazi Party, Einstein emigrated to the United States, where he continued to advance scientific thought. His research significantly influenced the development of atomic energy, marking a critical juncture in both science and global politics. In his later years, Einstein dedicated himself to the pursuit of a unified field theory, seeking to reconcile the fundamental forces of nature.

Einstein passed away in April 1955 at the age of 76. His insatiable curiosity and innovative spirit have solidified his legacy as one of the most influential physicists of the 20th century, shaping the trajectory of modern physics and our understanding of the universe.

Early Life, Family, and Education

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany, into a secular Jewish family. His father, Hermann Einstein, was a salesman and engineer who co-founded Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie, a Munich-based company specializing in the mass production of electrical equipment. His mother, Pauline Koch, managed the household, while Einstein had one sister, Maja, who was born two years after him.

Einstein began his education at the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich. However, he often felt alienated by the institution’s rigid pedagogical methods, which did not align with his learning style. Additionally, he experienced difficulties with speech during his early years. Despite these challenges, he developed a profound passion for classical music and the violin, interests that would remain significant throughout his life. Most notably, his formative years were characterized by a deep sense of curiosity and a desire to understand the world around him.

In the late 1880s, Max Talmud, a Polish medical student who occasionally dined with the Einstein family, became an informal tutor to young Albert. Talmud introduced him to a children’s science text that ignited Einstein’s fascination with the nature of light. This inspiration led him to write what would be recognized as his first significant paper, titled “The Investigation of the State of Aether in Magnetic Fields.”

In the mid-1890s, following the loss of a crucial business contract, Hermann relocated the family to Milan, Italy. Albert, however, remained in Munich to complete his studies at Luitpold. As he approached the age of military service, Einstein reportedly withdrew from classes, using a doctor’s note to cite nervous exhaustion as his reason for absence. When he rejoined his family in Italy, his parents were supportive of his perspective but harbored concerns about his future as a school dropout and draft dodger.

Ultimately, Einstein gained admission to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, attributed largely to his exceptional performance in mathematics and physics on the entrance examination. He first needed to complete his pre-university education, attending a high school in Aarau, Switzerland, under the guidance of Jost Winteler. During this time, Einstein lived with Winteler’s family and developed romantic feelings for Winteler’s daughter, Marie. At the dawn of the new century, he renounced his German citizenship and became a Swiss citizen.

Einstein’s IQ

While Albert Einstein’s intelligence quotient (IQ) is estimated to be around 160, there is no definitive record of him undergoing any formal testing. The first edition of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), which evolved into the commonly used WAIS-IV, was released in 1955, shortly before Einstein’s death. The maximum score on this test is 160, with scores of 135 or higher qualifying individuals for the 99th percentile.

In the late 1980s, magazine columnist Marilyn vos Savant was recognized in the Guinness Book of World Records for having the highest recorded IQ at 228. However, Guinness subsequently discontinued this category due to ongoing debates about the accuracy of IQ testing. Among those believed to have possessed higher IQs than Einstein are notable figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, Marie Curie, Nikola Tesla, and Nicolaus Copernicus.

Patent Clerk

After completing his university education, Albert Einstein encountered significant obstacles in securing academic positions, having strained relationships with some professors due to his preference for independent study over regular class attendance.

In 1902, he ultimately secured a stable position as a clerk at a Swiss patent office, thanks to a referral. This role provided Einstein with the opportunity to delve deeper into the ideas he had begun exploring during his studies, which laid the groundwork for his groundbreaking theories on the principle of relativity.

The year 1905 is often referred to as Einstein’s “miracle year,” during which he published four seminal papers in the prestigious journal Annalen der Physik. Two of these papers addressed the photoelectric effect and Brownian motion, while the other two introduced the now-famous equation E=mc2E=mc^2E=mc2 and the special theory of relativity, both of which were pivotal in shaping Einstein’s career and advancing the field of physics.

Inventions and Discoveries

As a physicist, Einstein made numerous significant contributions, but he is most renowned for his theory of relativity and the equation E=mc2E=mc^2E=mc2, which presaged the advent of atomic power and the atomic bomb.

Theory of Relativity

Einstein first introduced his special theory of relativity in 1905 in the paper “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” which revolutionized the understanding of physics. This theory posits that space and time are interconnected, forming a unified structure known as space-time.

By November 1915, Einstein had completed the general theory of relativity, which established a framework for understanding the relationship between gravity and space-time. He viewed this theory as the pinnacle of his research, as it allowed for more precise predictions of planetary orbits than those provided by Isaac Newton’s theories. General relativity offered a comprehensive and nuanced explanation of gravitational forces. Its validity was confirmed by British astronomers Sir Frank Dyson and Sir Arthur Eddington during the 1919 solar eclipse, marking Einstein’s emergence as a global scientific icon. Today, the principles of relativity are fundamental to the functionality of technologies such as GPS.

However, Einstein initially erred in his conception of the universe while formulating his general theory, which inherently suggested that the universe is either expanding or contracting. He resisted this notion, favoring the idea of a static universe, and introduced a “cosmological constant” to reconcile his equations with this belief. Subsequent developments in cosmology, particularly through the work of astronomer Edwin Hubble, demonstrated that the universe is indeed expanding. Hubble and Einstein met at the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1931 to discuss these findings.

In 2018, decades after Einstein’s passing, scientists confirmed a key aspect of his general theory: light from a star passing close to a black hole would be elongated to longer wavelengths due to the intense gravitational field. Observations of star S2 showed that its orbital velocity surged to over 25 million kilometers per hour as it approached the supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s center, causing its light to shift from blue to red as the wavelengths stretched to escape the gravitational pull.

Einstein’s E=mc2E=mc^2E=mc2

In his 1905 paper on the relationship between matter and energy, Einstein proposed the equation E=mc2E=mc^2E=mc2, which indicates that the energy (E) of a body is equal to its mass (M) multiplied by the square of the speed of light (C²). This groundbreaking equation implied that minute particles of matter could be converted into vast amounts of energy, heralding the era of atomic power.

The renowned quantum theorist Max Planck supported Einstein’s assertions, leading to his rise as a prominent figure in academia and on the lecture circuit. He held various positions before becoming the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (now known as the Max Planck Institute for Physics) from 1917 to 1933.

Nobel Prize in Physics

In 1921, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, as his theories on relativity were still viewed with skepticism at that time. Although he was not presented with the award until the following year due to bureaucratic delays, he chose to discuss relativity during his acceptance speech, reflecting his unwavering commitment to this revolutionary field of study.

Wives and Children

Albert Einstein married Mileva Marić on January 6, 1903. While studying in Zurich, Einstein met Marić, a Serbian physics student, and their relationship deepened despite strong opposition from his parents, who disapproved of her ethnic background. Undeterred, Einstein and Marić corresponded extensively, sharing thoughts on science and their future together. Following the death of Einstein’s father in 1902, the couple married shortly thereafter.

Together, they had three children. Their daughter, Lieserl, was born in 1902, prior to their marriage, and her fate remains unclear; she may have been raised by Marić’s relatives or placed for adoption. The couple also had two sons: Hans Albert Einstein, who became a distinguished hydraulic engineer, and Eduard “Tete” Einstein, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his youth.

The marriage, however, was fraught with challenges, leading to their divorce in 1919. Marić experienced an emotional breakdown linked to the separation. As part of their settlement, Einstein agreed to allocate any future Nobel Prize winnings to Marić.

During his marriage to Marić, Einstein began an affair with his cousin, Elsa Löwenthal. They married in 1919, coinciding with Einstein’s divorce, yet he continued to engage in extramarital relationships throughout their union, which ended with Löwenthal’s death in 1936.

Travel Diaries

In his forties, Einstein embarked on extensive travels, documenting his experiences in two volumes titled The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein.

The first volume, published in 2018, chronicles a five-and-a-half-month journey through the Far East, Palestine, and Spain. In autumn 1922, Einstein and Elsa set sail from Marseille, France, on their voyage to Japan, traversing the Suez Canal and visiting locations such as Sri Lanka, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai before returning to Germany via Palestine and Spain in March 1923.

The second volume, released in 2023, details a three-month lecture tour in Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil in 1925.

These diaries reveal unflattering assessments of various cultures, including his views on the Chinese, Sri Lankans, and Argentinians, which stands in contrast to his later vocal opposition to racism. For instance, in a November 1922 entry, he described residents of Hong Kong as “industrious, filthy, lethargic people.”

Becoming a U.S. Citizen

In 1933, Einstein accepted a position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he would remain for the rest of his life. This move coincided with the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, which propagated violent anti-Semitism and branded Einstein’s work as “Jewish physics.” As Jewish citizens faced increasing discrimination and were barred from academic and official positions, Einstein himself became a target for assassination. In response, many scientists from Europe fled to the United States due to concerns over Nazi plans for atomic weaponry.

Upon relocating and beginning his tenure at the Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein expressed admiration for the American meritocracy and the freedoms afforded to individuals—a stark contrast to his earlier experiences in Germany. By 1935, he had obtained permanent residency, and he became an American citizen five years later.

In the United States, Einstein primarily focused on developing a unified field theory aimed at reconciling the various laws of physics. However, during World War II, he also contributed to military projects related to naval weaponry and made substantial monetary donations to the war effort by auctioning manuscripts worth millions.

Einstein and the Atomic Bomb

In 1939, Albert Einstein and fellow physicist Leo Szilard wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to inform him of the potential development of an atomic bomb by Nazi Germany. Their correspondence aimed to galvanize the United States into action, prompting the creation of its own nuclear weapons program.

This initiative ultimately led to the establishment of the Manhattan Project. However, Einstein did not directly participate in its implementation, primarily due to his pacifist beliefs and socialist affiliations. Furthermore, he faced significant scrutiny and distrust from J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI director at the time. In July 1940, the U.S. Army Intelligence Office denied Einstein a security clearance for the project, resulting in a prohibition against consultation with J. Robert Oppenheimer and the scientists at Los Alamos.

Einstein was unaware of the United States’ plans to deploy atomic bombs against Japan in 1945. Upon learning about the bombing of Hiroshima, he reportedly expressed his dismay, stating, “Ach! The world is not ready for it.”

Following the war, Einstein emerged as a prominent advocate for nuclear disarmament. In 1946, he and Szilard founded the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists. Through an essay published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1947, Einstein emphasized the importance of international cooperation, advocating for the United Nations to oversee nuclear weapons as a means of deterring conflict rather than facilitating it.

Time Travel and Quantum Theory

Following World War II, Albert Einstein dedicated himself to the pursuit of his unified field theory and further exploration of significant elements of his general theory of relativity, such as time travel, wormholes, black holes, and the origins of the universe. Despite his groundbreaking contributions, Einstein experienced a sense of isolation in his work, as many of his contemporaries shifted their focus to quantum theory. In the final decade of his life, he increasingly withdrew from public attention, choosing instead to remain in Princeton and engage in intellectual discourse with a select group of colleagues.

Personal Life

In the late 1940s, Einstein became an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), recognizing the parallels between the persecution of Jews in Germany and the discrimination faced by Black individuals in the United States. He corresponded with prominent figures such as scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois and performer Paul Robeson, advocating for civil rights and denouncing racism as a “disease” during a speech at Lincoln University in 1946.

Einstein was notably meticulous about his sleep, claiming a requirement of ten hours per night for optimal functioning. He famously stated that his theory of relativity was inspired by a dream involving cows being electrocuted. Regular naps were a part of his routine, and he would often hold small objects, like a spoon or a pencil, in his hand as he drifted to sleep. This practice allowed him to awaken before reaching deeper stages of sleep, a hypnagogic state that is believed to enhance creativity and facilitate the capture of sleep-inspired ideas.

While sleep held great importance for Einstein, he famously eschewed socks. He expressed his disdain for wearing them in a letter to his future wife, Elsa, citing irritation caused by his big toe pushing through the material. One of the most iconic images of the 20th century captures Einstein playfully sticking out his tongue as he departed his 72nd birthday celebration on March 14, 1951. This moment occurred when a throng of reporters and photographers approached him for a smile after an evening of festivities. Tired of posing, he cheekily responded with a gesture that was immortalized by UPI photographer Arthur Sasse. Amused by the photograph, Einstein later ordered several prints to share with friends, and one signed copy fetched $125,000 at auction in 2017.

Death and Final Words

Einstein passed away on April 18, 1955, at the age of 76 at the University Medical Center at Princeton. The day before his death, while preparing a speech to commemorate Israel’s seventh anniversary, he suffered an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Although he was hospitalized for treatment, he declined surgery, expressing a desire to accept his fate. “I want to go when I want,” he remarked. “It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.”

In the moments leading up to his death, Einstein reportedly muttered a few words in German, but their translation was lost as the attending nurse did not speak the language. Ralph Morse, a photographer for Life magazine, recounted in a 2014 interview that the hospital was inundated with journalists and curious onlookers following the announcement of Einstein’s death. Seeking to capture the essence of the moment, he gained access to Einstein’s office at the Institute for Advanced Studies, offering alcohol to the superintendent. He photographed the office exactly as it was left by Einstein.

After an autopsy, Einstein’s body was transported to a funeral home in Princeton and subsequently cremated in Trenton, New Jersey. Morse noted that he was the only photographer present for the cremation; however, Life’s managing editor, Ed Thompson, opted not to publish an exclusive story at the request of Einstein’s son, Hans.

Einstein’s Brain: A Study of Genius

During the autopsy of Albert Einstein, pathologist Thomas Stoltz Harvey removed his brain for preservation and future research, reportedly without the consent of Einstein’s family. Despite this controversy, Einstein had previously participated in brain studies and, according to at least one biography, expressed a desire for researchers to examine his brain posthumously. Following his wishes, the remainder of his body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at a secret location.

In 1999, a team of Canadian scientists studying Einstein’s brain discovered that his inferior parietal lobe, a region associated with spatial relationships, three-dimensional visualization, and mathematical reasoning, was 15 percent wider than that of individuals with typical intelligence. These findings, reported by The New York Times, suggest that this anatomical difference may provide insights into the exceptional intellectual capabilities that Einstein exhibited.

In 2011, the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia received thin slices of Einstein’s brain from Dr. Lucy Rorke-Adams, a neuropathologist affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. These slices, which Dr. Rorke-Adams obtained from Harvey, were subsequently put on display, furthering the exploration of the neurological underpinnings of genius.

Einstein in Literature and Film: A Comprehensive Overview

Since the passing of Albert Einstein, an extensive body of literature has emerged, exploring the life and contributions of this iconic thinker. Notable works include Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson and Einstein: A Biography by Jürgen Neffe, both published in 2007. Additionally, Einstein’s own reflections are captured in the collection The World As I See It, providing insights into his thoughts and philosophy.

Einstein’s impact extends beyond the written word; he has also been depicted in various cinematic portrayals. In the 1985 film Insignificance, Michael Emil portrayed a character referred to as “The Professor,” a clear nod to Einstein. The film features alternate versions of notable figures, including Marilyn Monroe, Joe DiMaggio, and Joseph McCarthy, intersecting in a New York City hotel setting.

In the realm of comedy, Walter Matthau brought Einstein to life in the 1994 film I.Q., where he takes on the role of a matchmaker for his niece, played by Meg Ryan. Other lesser-known films, such as I Killed Einstein, Gentlemen (1970) and Young Einstein (1988), also include interpretations of the famed physicist.

For a more historically accurate representation, the 2017 National Geographic miniseries Genius provided a compelling narrative of Einstein’s life. This ten-part series featured Johnny Flynn as a younger Einstein and Geoffrey Rush as the older scientist, following his escape from Germany. The series was directed by Ron Howard, emphasizing both the personal and professional challenges faced by Einstein.

The latest portrayal of Einstein is found in the 2023 biopic Oppenheimer, directed by Christopher Nolan. In this film, Tom Conti plays Einstein, who interacts with Cillian Murphy’s character, J. Robert Oppenheimer, during the critical period of the Manhattan Project. This contemporary depiction underscores Einstein’s enduring relevance in discussions of science and ethics.