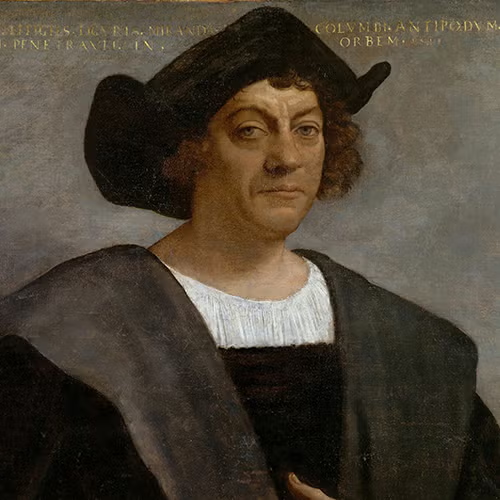

Who Was Christopher Columbus?

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator whose voyages across the Atlantic Ocean significantly impacted world history. In 1492, he embarked on his first expedition from Spain aboard the Santa Maria, accompanied by the Pinta and the Niña, with the objective of establishing a new route to Asia. Instead of reaching Asia, Columbus and his crew landed on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming the territory for Spain and inadvertently “discovering” the Americas. Over the course of his life, he undertook three additional voyages to the Caribbean and South America, continuing to believe until his death that he had found a shorter path to Asia. Columbus is often credited—and critiqued—for paving the way for European colonization of the Americas.

Where Was Columbus Born?

Christopher Columbus, known in Italian as Cristoforo Colombo, was born in 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, which is now part of Italy. He was the son of Domenico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa and had four siblings: Bartholomew, Giovanni, Giacomo, and a sister named Bianchinetta. As a young man, Columbus worked as an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business while also studying sailing and mapmaking. In his 20s, he relocated to Lisbon, Portugal, before eventually settling in Spain, which would serve as his home base for the remainder of his life.

First Voyages

Columbus began his seafaring career as a teenager, taking part in several trading voyages throughout the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas. One notable voyage to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him closer to Asia than any other journey he undertook.

His first venture into the Atlantic Ocean in 1476 proved perilous; while sailing with a commercial fleet, he faced a life-threatening situation when French privateers attacked off the coast of Portugal. After his ship was set ablaze, Columbus swam to safety on Portuguese shores.

Eventually, he made his way to Lisbon, where he married Filipa Perestrelo, and the couple welcomed their son, Diego, around 1480. Following Filipa’s untimely death when Diego was still young, Columbus moved to Spain and fathered a second son, Fernando, born out of wedlock in 1488 with Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.

Through various expeditions to Africa, Columbus gained crucial knowledge about the Atlantic currents that flow east and west from the Canary Islands, which would later inform his transatlantic voyages.

Columbus’ 1492 Route and Ships

The Asian islands near China and India were renowned for their spices and gold, making them highly desirable destinations for European explorers. However, the dominance of Muslim powers over trade routes in the Middle East complicated eastward travel. To circumvent these challenges, Christopher Columbus devised a westward route across the Atlantic, believing it would be quicker and safer. He estimated the Earth to be spherical, calculating the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan to be approximately 2,300 miles.

Many contemporary nautical experts disagreed with Columbus’s estimates. They adhered to the second-century BCE calculation of the Earth’s circumference at 25,000 miles, which placed the actual distance between the Canary Islands and Japan at about 12,200 statute miles. Despite their skepticism regarding the distance, they concurred that a westward journey from Europe would provide an uninterrupted maritime route.

Columbus proposed a three-ship expedition first to the Portuguese king, then to the city-states of Genoa and Venice, but he faced rejection each time. In 1486, he approached the Spanish monarchs, Queen Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. Their focus on the Reconquista and doubts from their nautical experts initially led to further rejection. However, the idea intrigued the monarchs, and Columbus was retained at court. Following the Spanish capture of Granada in January 1492, Columbus successfully secured funding for his expedition.

In late August 1492, Columbus departed Spain from the port of Palos de la Frontera aboard three ships: the Santa Maria, a larger carrack commanded by Columbus, accompanied by the Pinta and the Niña, both smaller Portuguese caravels.

Where Did Columbus Land in 1492?

On October 12, 1492, after 36 days of sailing westward, Columbus and several crew members landed on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming it for Spain. They encountered a friendly group of indigenous people who were willing to trade. Exchanges included glass beads, cotton balls, parrots, and spears, with the Europeans noticing the gold adornments worn by the natives.

Columbus continued his exploration, visiting Cuba—mistakenly believed to be mainland China—and Hispaniola, which he thought might be Japan. During this journey, the Santa Maria ran aground on a reef off the coast of Hispaniola. With assistance from local islanders, Columbus’s men salvaged materials from the wreck to establish a settlement named Villa de la Navidad, or “Christmas Town,” using timber from the ship. Columbus left 39 men to occupy the settlement, convinced he had reached Asia before returning to Spain with the two remaining ships. Upon his arrival in 1493, he presented an embellished account of his discoveries and was warmly received by the royal court.

Later Voyages Across the Atlantic

In 1493, Columbus embarked on his second expedition, exploring more islands in the Caribbean. Upon reaching Hispaniola, he discovered that the Navidad settlement had been destroyed, and all the sailors had been massacred. Ignoring the wishes of the local queen, Columbus enforced a forced labor policy on the indigenous population to rebuild the settlement and search for gold, resulting in limited gold finds and significant resentment among the native inhabitants.

Before returning to Spain, Columbus left his brothers, Bartholomew and Giacomo, to govern the settlement on Hispaniola. He sailed briefly around larger Caribbean islands, further convincing himself that he had discovered the outer islands of China.

It was not until his third voyage that Columbus reached the South American mainland, exploring the Orinoco River in present-day Venezuela. By this time, conditions at the Hispaniola settlement had deteriorated, leading to near-mutiny among the settlers, who felt misled by Columbus’s promises of riches and were dissatisfied with the management of his brothers. The Spanish Crown responded by sending a royal official to arrest Columbus and strip him of his authority. He returned to Spain in chains but eventually had the charges dropped, though he lost his titles as governor of the Indies and much of his accumulated wealth.

Convinced by Columbus that another voyage could yield the promised riches, King Ferdinand authorized a fourth and final expedition in 1502. Columbus navigated along the eastern coast of Central America, seeking a route to the Indian Ocean. A storm wrecked one of his ships, leaving the captain and crew stranded on Cuba. During this period, local islanders, weary of the Spaniards’ poor treatment, refused to provide food.

In a moment of inspiration, Columbus consulted an almanac and devised a plan to “punish” the islanders by predicting a lunar eclipse. On February 29, 1504, the eclipse alarmed the natives enough to restore trade relations with the Spaniards. A rescue party finally arrived in July, sent by the royal governor of Hispaniola, and Columbus and his men returned to Spain in November 1504.

In his final years, Columbus struggled to regain his reputation. While he recovered some of his riches in May 1505, he never regained his former titles.

How Did Columbus Die?

Columbus died on May 20, 1506, in Valladolid, Spain, likely from severe arthritis following an infection. At the time of his death, he still believed he had discovered a shorter route to Asia. The location of his burial site remains uncertain. His remains were moved several times over 400 years—from Valladolid to Seville in 1509; then to Santo Domingo in 1537; to Havana in 1795; and back to Seville in 1898. Consequently, both Seville and Santo Domingo claim to be the true burial site of Columbus, with the possibility that his bones were intermingled with those of others during these transfers.

Santa Maria Discovery Claim

In May 2014, Columbus made headlines once more when archaeologists claimed to have located the Santa Maria off the north coast of Haiti. Barry Clifford, the expedition’s leader, asserted that “all geographical, underwater topography and archaeological evidence strongly suggests this wreck is Columbus’ famous flagship.” However, subsequent investigations by UNESCO determined that the wreck was from a later period and located too far from shore to be the legendary ship.

Columbian Exchange: A Complex Legacy

Columbus is often credited with opening the Americas to European colonization, yet he is equally blamed for the destruction of indigenous populations in the regions he explored. His expeditions initiated the Columbian Exchange, a widespread transfer of people, plants, animals, diseases, and cultures that profoundly affected societies globally.

The introduction of horses from Europe enabled Native American tribes in the Great Plains to transition from nomadic lifestyles to hunting. Wheat from the Old World quickly became a staple food source in the Americas. Additionally, coffee from Africa and sugarcane from Asia emerged as significant cash crops for Latin American countries, while indigenous crops such as potatoes, tomatoes, and corn became vital staples in Europe, contributing to population growth.

However, the Columbian Exchange also introduced new diseases to both hemispheres, with the most devastating impact felt in the Americas. Smallpox, in particular, decimated Native American populations, significantly facilitating European domination. The initial benefits of the Columbian Exchange largely favored Europeans, ultimately altering the Americas and erasing many vibrant Indigenous cultures.

Columbus Day: An Evolving Holiday

In the 19th century, as a wave of Italian immigrants settled in the United States, they faced significant discrimination, including the mass lynching of 11 Sicilian immigrants in New Orleans in 1891. In response, President Benjamin Harrison called for the first national observance of Columbus Day on October 12, 1892, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. This gesture was seen as a means for Italian Americans to gain acceptance.

Colorado became the first state to officially observe Columbus Day in 1906, followed by 14 other states within five years. By joint resolution of Congress, it was declared a federal holiday in 1934 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1970, Congress designated the holiday to be celebrated on the second Monday in October.

However, as criticism of Columbus’s legacy—especially regarding his impact on Indigenous civilizations—grew, participation in Columbus Day celebrations diminished. As of 2023, approximately 29 states no longer observe Columbus Day, and around 195 cities have renamed the holiday or replaced it with Indigenous Peoples Day. Although Indigenous Peoples Day is not an official holiday, its observance was recognized by the federal government in 2022 and 2023, with President Joe Biden describing it as “a day in honor of our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this nation.”

One notable city that has moved away from celebrating Columbus Day is Columbus, Ohio, named after the explorer. In 2018, Mayor Andrew Ginther announced that the city would remain open on Columbus Day, instead honoring Veterans Day. In July 2020, the city also removed a large metal statue of Columbus from in front of City Hall.