Table of Contents

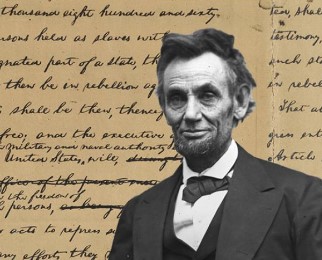

Who Was Abraham Lincoln?

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, served from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. He is widely celebrated as one of America’s most influential figures, primarily for his leadership during the Civil War and his pivotal role in the abolition of slavery. Lincoln’s dedication to preserving the Union and his firm belief in democracy exemplified the ideals of self-government, which resonate globally. In 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which liberated enslaved people across the Confederate states. Lincoln’s journey from humble beginnings to the presidency remains one of the nation’s most inspiring stories. Tragically, his life was cut short when he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth in April 1865, at the age of 56, just as the nation was beginning to heal and reunite. His legacy as a compassionate and visionary leader endures to this day.

Early Life, Parents, and Education

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln in a log cabin in rural Hodgenville, Kentucky. Thomas, a determined and hardworking pioneer, managed to achieve a modest level of prosperity and was respected in the local community. Abraham had two siblings: his older sister Sarah and his younger brother Thomas, who tragically died in infancy.

In 1817, the Lincoln family faced a significant hardship when they were forced to leave their home in Kentucky due to a land dispute. They relocated to Perry County, Indiana, where they “squatted” on public land, building a simple shelter and subsisting through farming and hunting. Eventually, Thomas Lincoln was able to purchase the land they had been working.

When Abraham was nine years old, his mother, Nancy, died of milk sickness on October 5, 1818. This loss deeply affected the young boy, leading him to become more withdrawn and resentful of the hard labor expected of him. In December 1819, just over a year after Nancy’s death, Thomas remarried Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow from Kentucky who had three children of her own. Sarah was a kind and nurturing woman, and she formed a close bond with Abraham, who came to respect her deeply.

Although both of his biological parents were likely illiterate, Sarah encouraged Abraham to read. Despite the scarcity of books in the remote Indiana wilderness, Abraham took every opportunity to learn. He reportedly walked miles to borrow books and read widely, including the Bible, Robinson Crusoe, Pilgrim’s Progress, and Aesop’s Fables. Lincoln’s formal education amounted to roughly 18 months in total, often in short intervals when he could attend school.

In March 1830, the Lincoln family moved once again, this time to Macon County, Illinois. By the time they relocated to Coles County, Abraham, now 22 years old, had begun to support himself through manual labor, signaling the start of his independent adult life.

How Tall Was Abraham Lincoln?

Abraham Lincoln stood at 6 feet 4 inches, a height that made him notably tall for his time. Despite his rawboned, lanky appearance, he was also muscular and physically strong. His deep backwoods twang complemented his long-striding gait, a reflection of his rugged background. Known for his impressive strength, Lincoln had a reputation for skillfully wielding an ax, earning his living in his early years by splitting wood for fire and constructing rail fences.

Wrestling Hobby and Legal Career

As a young man, Lincoln moved to the small community of New Salem, Illinois, where he worked various jobs, including shopkeeper, postmaster, and general store owner. It was through his interactions with the local population that Lincoln developed his social skills and honed the storytelling ability that would later contribute to his popularity.

Given his imposing physique, Lincoln was also an accomplished wrestler. Over the course of 12 years, he only suffered one recorded loss—against Hank Thompson in 1832. Lincoln’s wrestling abilities were well-known, and a local shopkeeper who employed him even arranged matches as a promotional strategy. Lincoln’s most notable victory came against the local champion, Jack Armstrong, which helped elevate his status within the community. In recognition of his prowess, the National Wrestling Hall of Fame awarded Lincoln its Outstanding American Award posthumously in 1992.

When the Black Hawk War erupted in 1832, Lincoln was elected captain of a volunteer company. Though he did not see combat, his time as a militia leader allowed him to make significant political connections.

At the start of his political career, Lincoln decided to pursue law. He taught himself the principles of law through William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. After passing the bar in 1837, Lincoln relocated to Springfield, Illinois, to practice law with the John T. Stuart firm. By 1844, he partnered with William Herndon, and although their legal philosophies differed, they formed a close professional and personal bond.

While Lincoln initially made a good income as a lawyer, Springfield’s limited legal work prompted him to follow the court’s circuit through Illinois’ county seats, which provided additional opportunities.

Wife and Children

On November 4, 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd, a well-educated, strong-willed woman from a prominent Kentucky family. Their relationship, however, was marked by periods of instability. Though engaged in 1840, many of their friends and family were puzzled by their union, and Lincoln himself had doubts at times. In 1841, the engagement was briefly broken off, most likely at Lincoln’s initiative. After a later meeting at a social event, the couple reconciled and married.

Lincoln and Mary Todd had four sons: Robert Todd, Edward Baker, William Wallace, and Thomas “Tad.” Of these, only Robert survived to adulthood. Before his marriage to Mary Todd, Lincoln had been romantically involved with Anne Rutledge, whom he met around 1837. However, their potential engagement was cut short when Rutledge died of typhoid fever at the age of 22, a loss that reportedly left Lincoln deeply saddened. Historians, however, debate the extent of their relationship and the depth of Lincoln’s grief.

After Rutledge’s death, Lincoln briefly courted Mary Owens, but the engagement was eventually broken off.

Political Career

Abraham Lincoln’s political career began in 1834 when he was elected to the Illinois state legislature as a member of the Whig Party. More than a decade later, from 1847 to 1849, he served a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives. His time in national politics was brief and largely unremarkable, as he was the lone Whig from Illinois, which left him with few political allies.

During his congressional tenure, Lincoln voiced opposition to the Mexican-American War and supported Zachary Taylor for president in 1848. His criticism of the war was unpopular in Illinois, leading him to decline a second term and return to Springfield to resume his legal practice.

In the 1850s, as the railroad industry expanded westward, Illinois became a central hub for new businesses. Lincoln served as a lobbyist and attorney for the Illinois Central Railroad, and his success in several high-profile cases led to a growing client base that included banks, insurance companies, and manufacturers. Lincoln’s courtroom success also extended to criminal trials, most notably when he defended a man accused of murder by disproving a key eyewitness testimony using an almanac.

Lincoln and Slavery

In the Illinois state legislature, Lincoln supported Whig policies promoting government-sponsored infrastructure projects and protective tariffs. These early political views laid the foundation for his stance on slavery, which he initially saw as an impediment to economic progress rather than a moral issue.

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed individual states and territories to decide whether to permit slavery, ignited violent opposition and contributed to the formation of the Republican Party. This development reignited Lincoln’s political passions, and his views on slavery began to shift toward moral opposition. By 1856, Lincoln joined the Republican Party.

In 1857, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, which ruled that Black people were not citizens and had no inherent rights, prompted Lincoln to further clarify his beliefs. While he acknowledged that Black people were not equal to whites, he maintained that the founding principles of the nation recognized the inherent rights of all men.

Senate Race

In 1858, Lincoln challenged incumbent U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas for his seat. Lincoln’s nomination acceptance speech condemned Douglas, the Supreme Court, and President James Buchanan for their support of slavery, declaring that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Lincoln and Douglas participated in a series of seven debates across Illinois, where they sparred over issues such as states’ rights, western expansion, and, most notably, slavery. The debates were widely covered in the press, and although Douglas was re-elected by the Illinois legislature, Lincoln’s performance garnered national attention and propelled him into the political spotlight.

U.S. President

In 1860, with his political profile on the rise, Lincoln became the Republican nominee for president. At the Republican National Convention in Chicago on May 18, he surpassed better-known figures like William Seward and Salmon P. Chase due to his moderate stance on slavery, support for national infrastructure improvement, and advocacy for protective tariffs.

In the November 1860 election, Lincoln triumphed in a four-way race against Douglas, John C. Breckinridge, and John Bell, securing nearly 40 percent of the popular vote and 180 of 303 Electoral College votes, which granted him the presidency. Lincoln grew his signature beard following his election.

Lincoln’s Cabinet

Upon his election, Lincoln formed a cabinet consisting of many of his political rivals, including William Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Edwin Stanton. His leadership approach was encapsulated by the adage, “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.” This diverse cabinet proved to be one of Lincoln’s greatest assets during his first term, particularly as the nation edged closer to war.

Civil War Begins

Before Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1861, seven Southern states had seceded from the Union. By April, the U.S. military installation at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, was under siege. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on the fort, marking the beginning of the Civil War.

As president, Lincoln wielded unprecedented powers to preserve the Union. He allocated $2 million for war materials without congressional approval, called for 75,000 volunteers to serve in the military without a formal declaration of war, and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, allowing for the detention of suspected Confederate sympathizers without warrants.

Despite facing intense opposition, Lincoln’s resolve to reunite the nation never wavered. He was frequently at odds with his generals, cabinet, and even his party, yet he remained steadfast in his commitment to preserving the Union.

Emancipation Proclamation

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, transforming the Civil War’s purpose from solely preserving the Union to also abolishing slavery. The Union Army’s early defeats had made it difficult to maintain morale, but the victory at Antietam in September 1862 gave Lincoln the confidence to make this bold declaration. The Proclamation declared that all enslaved individuals in rebel-held territories “shall be free.”

While the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free all enslaved individuals—its application was limited to states in rebellion and excluded border states and certain territories—it had significant symbolic value. It also allowed Black Americans to enlist in the Union Army, which helped secure the Union victory. The Proclamation set the stage for the passage of the 13th Amendment, which permanently abolished slavery in the United States.

Gettysburg Address

On November 19, 1863, Lincoln delivered his most famous speech at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery in Pennsylvania, following one of the Civil War’s bloodiest battles. In his 272-word address, Lincoln framed the war as a test of the nation’s commitment to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence, particularly the idea that all men are created equal. He urged the living to ensure that the government “of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The Gettysburg Address not only reinforced the Union’s mission to preserve the nation but also expanded the war’s purpose to include the abolition of slavery and the promotion of equality for all Americans.

Civil War Ends and Lincoln’s Reelection

Following the issuance of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Northern war effort steadily improved, though it progressed more through attrition than through decisive military victories. By 1864, Confederate forces had evaded a major defeat, and President Lincoln, uncertain of his political future, believed he would serve only a single term. His political rival, George B. McClellan, former commander of the Army of the Potomac, challenged Lincoln in the presidential race. However, the election was not close. Lincoln secured 55 percent of the popular vote and won 212 out of 243 electoral votes.

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, effectively marking the end of the Civil War. Although the war was winding down, the process of Reconstruction began in Union-controlled territories as early as 1863. Lincoln supported a policy of rapid reunification with minimal punishment for former Confederates. However, a faction of radical Republicans in Congress called for full repentance and allegiance from the South. Before a political resolution could materialize, Lincoln was assassinated.

Assassination and Funeral

Abraham Lincoln was tragically assassinated on the evening of April 14, 1865, by the actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Lincoln was rushed to the Petersen House across the street, where he succumbed to his wounds the following morning. He was 56 years old. His death was deeply mourned by citizens throughout the North and South.

Lincoln’s body lay in state at the U.S. Capitol, where 600 invited guests attended a funeral in the White House on April 19. Despite the public mourning, an inconsolable Mary Todd Lincoln was not present. Lincoln’s body was then transported to Springfield, Illinois, in a funeral procession. The train carrying his remains made stops in cities along the route, where memorial services were held. Lincoln was finally interred in his tomb on May 4, 1865.

On the same day as Lincoln’s assassination, Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn in as the 17th president of the United States at the Kirkwood House in Washington.

Abraham Lincoln’s Hat

Abraham Lincoln’s tall stature and distinctive top hats made him instantly recognizable. Though the exact origin of his choice to wear top hats remains unclear, historians suggest it may have been a deliberate decision to enhance his image. Lincoln wore his top hat to Ford’s Theatre on the night of his assassination.

After his death, the War Department preserved the hat until 1867, when it was transferred to the Patent Office and the Smithsonian Institution with the approval of Mary Todd Lincoln. Initially stored in a basement to avoid public commotion, the hat was finally displayed at the Smithsonian in 1893 and has since become one of the institution’s most cherished artifacts.

Legacy

Abraham Lincoln is widely regarded as one of the greatest presidents in American history. A resolute leader, Lincoln utilized all available powers to secure Union victory in the Civil War and to abolish slavery. Some historians argue that without his leadership, the Union might not have been preserved. As historian Michael Burlingame notes, “No president in American history ever faced a greater crisis, and no president ever accomplished as much.”

Lincoln’s values are encapsulated in his Second Inaugural Address, where he urged national reconciliation: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

The Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial, dedicated in 1922, stands as a lasting tribute to Lincoln’s legacy. Modeled after the Greek Parthenon, the monument features a 19-foot statue of Lincoln and engravings of the Gettysburg Address and his Second Inaugural Address. Former President William Howard Taft chaired the Lincoln Memorial Commission, which oversaw its design and construction. Today, the memorial attracts around 8 million visitors annually and remains the most visited site in Washington, D.C. The steps of the memorial were famously the site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963.

Abraham Lincoln in Movies and TV

Abraham Lincoln has been portrayed in numerous films and television shows, ranging from biographical dramas to whimsical depictions. One of the earliest films, Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), starred Henry Fonda and focused on Lincoln’s early life and legal career. A year later, Abe Lincoln in Illinois dramatized his life after his move from Kentucky.

The most significant modern portrayal of Lincoln came in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012), where Daniel Day-Lewis earned an Academy Award for his performance as the president, and Sally Field portrayed Mary Todd Lincoln. The film was nominated for Best Picture.

More fantastical depictions of Lincoln include the 1989 comedy Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, in which Lincoln is portrayed as a time-traveling figure helping two high school students with their history project, and the 2012 action film Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, in which Lincoln leads a secret life hunting vampires during the Civil War.

Lincoln’s role in the Civil War was explored in the 1990 Ken Burns documentary The Civil War, which won numerous awards, including two Emmys and two Grammys. In 2022, the History Channel aired a three-part docuseries titled Abraham Lincoln, further cementing his historical and cultural impact.