Table of Contents

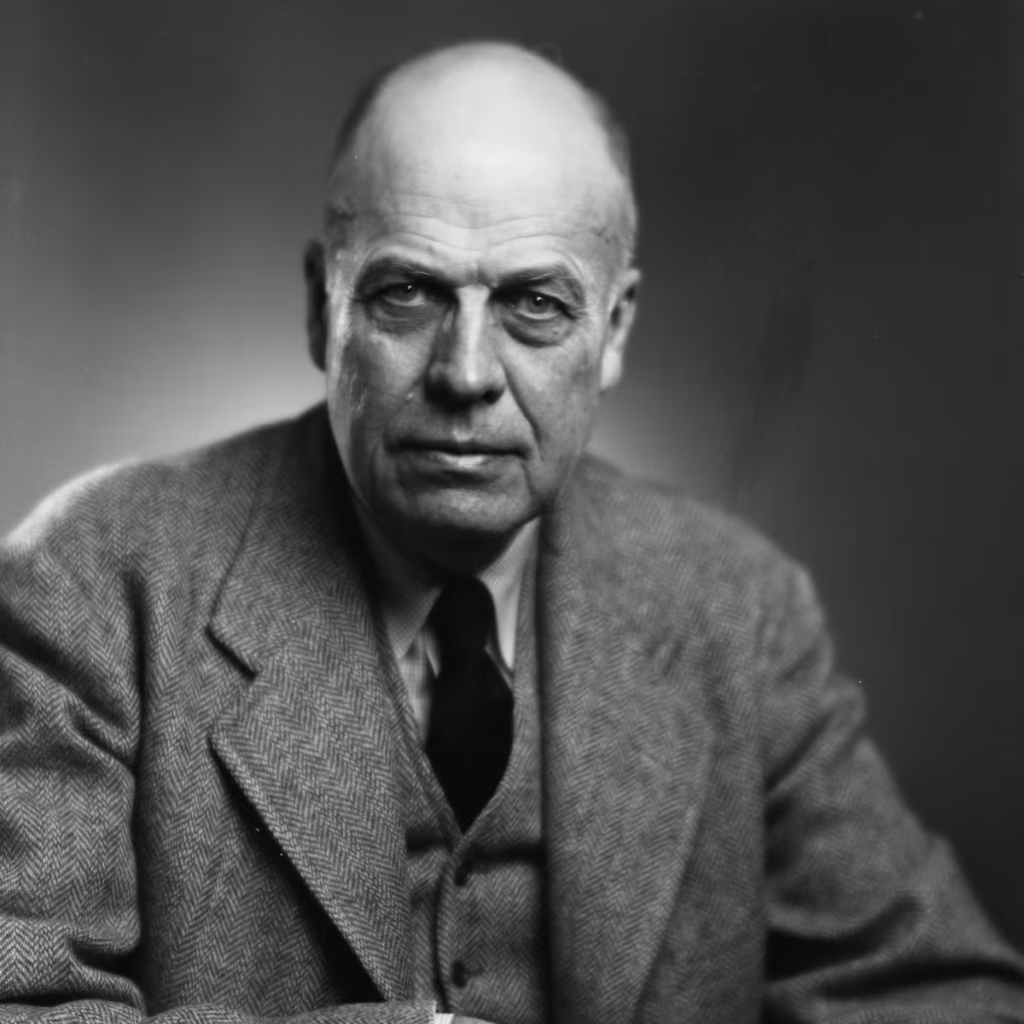

Who Was Edward Hopper?

Edward Hopper (1882–1967) was a prominent American realist painter and printmaker, celebrated for his evocative portrayals of modern life that often conveyed a profound sense of isolation and stillness. Trained as an illustrator, Hopper’s early career focused on advertising and etchings before he established himself as a masterful artist. His iconic works, including House by the Railroad (1925), Automat (1927), and Nighthawks (1942), remain defining pieces of 20th-century American art.

Early Life

Born on July 22, 1882, in Nyack, New York—a small shipbuilding community along the Hudson River—Edward Hopper grew up in a middle-class family that valued education and creativity. From a young age, Hopper displayed an aptitude for art, producing works that reflected his early interest in impressionism and pastoral themes. His talent was evident by age five, and he continued honing his skills throughout his school years. Among his earliest signed pieces is a rowboat painting from 1895.

Although initially envisioning a career as a nautical architect, Hopper shifted his focus to fine art. After graduating high school in 1899, he briefly studied illustration via correspondence before enrolling at the New York School of Art and Design. There, he learned under notable artists like William Merritt Chase, an American impressionist, and Robert Henri, a leading figure of the Ashcan School, which emphasized realism in art.

Early Career and Paintings

Hopper began his professional journey in 1905 as an illustrator for an advertising agency. While the work provided financial stability, he found it creatively limiting and pursued his own artistic endeavors. During this period, Hopper made several trips to Europe, including Paris and Spain, which deeply influenced his style. While movements like cubism and fauvism were gaining traction, Hopper gravitated toward impressionism, particularly admiring the works of Claude Monet and Édouard Manet. Their use of light and composition became hallmarks of Hopper’s later work.

Notable works from this period include Bridge in Paris (1906), Louvre and Boat Landing (1907), and Summer Interior (1909). Upon returning to the U.S., Hopper continued working as an illustrator while exhibiting his art. His participation in significant events such as the 1910 Exhibition of Independent Artists and the 1913 Armory Show, where he sold his first painting (Sailing, 1911), marked the beginning of his recognition as an artist. During this time, Hopper settled in Greenwich Village, New York, where he lived and worked for most of his life.

Wife and Muse

Around the early 1910s, the towering Edward Hopper (standing at 6’5″) began making regular summer trips to New England, a region known for its scenic beauty that provided ample inspiration for his impressionist-influenced paintings. Works such as Squam Light (1912) and Road in Maine (1914) emerged during this period. Despite a burgeoning career as an illustrator, Hopper struggled to garner significant interest in his own artwork throughout the decade. However, the dawn of the 1920s marked a turning point in his fortunes. At 37, Hopper held his first solo exhibition, arranged by art patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney at the Whitney Studio Club. The exhibition primarily featured Hopper’s Parisian scenes.

In 1923, while spending the summer in Massachusetts, Hopper reconnected with Josephine Nivison, a former classmate who had also achieved some success as a painter. The two married in 1924, and their personal and professional lives became closely intertwined. Often working side by side, they influenced each other’s artistic practices. Josephine, in particular, insisted that she be the sole model for any female figures in Hopper’s paintings, leading to her frequent presence in his work from this period onward.

Although later accounts, including those from Josephine’s diaries, portrayed the marriage as dysfunctional and marked by abuse from Hopper, these claims were contested by others who knew the couple well.

Josephine played a crucial role in Hopper’s transition from oil painting to watercolor, and she also helped expand his network within the art world. This led to a significant career breakthrough: a one-man show at the Rehn Gallery, where all of Hopper’s watercolors sold. The success of this exhibition allowed him to leave his illustration work behind, solidifying his relationship with the gallery for the remainder of his career.

Sought-After Art and ‘Nighthawks’

By the second half of his career, Hopper had reached a level of financial stability and critical acclaim, producing some of his most iconic works. He continued to paint in collaboration with Josephine, either in their Washington Square studio or during their frequent travels to New England and abroad. Notable pieces from this period include The Lighthouse at Two Lights (1929), depicting a tranquil lighthouse in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, and Automat (1927), which portrays a solitary woman in a New York City diner. The latter was exhibited at his second show at the Rehn Gallery, where its success further propelled Hopper’s reputation.

Another important work from this time is House by the Railroad (1925), a depiction of a Victorian mansion beside a railroad track. In 1930, it became the first painting acquired by the newly established Museum of Modern Art in New York. Three years later, Hopper was honored with a retrospective at the museum, underscoring the esteem in which his work was held.

Despite this growing success, Hopper’s most famous painting, Nighthawks (1942), would come later. The iconic image of three patrons and a waiter sitting in a brightly lit diner on a quiet, empty street has become synonymous with Hopper’s style, characterized by its stark composition, masterful use of light, and enigmatic narrative. Nighthawks was acquired almost immediately by the Art Institute of Chicago, where it remains on display today.

Accolades in Later Years and Death

As abstract expressionism rose to prominence in the mid-20th century, Hopper’s popularity began to decline. However, his reputation as a master of American realism remained intact. In 1950, he was honored with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and in 1952, he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition. A few years later, Hopper was featured in a Time magazine cover story, and in 1961, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy selected his painting House of Squam Light, Cape Ann to be displayed in the White House.

Despite declining health, which reduced his output, Hopper continued to produce significant works such as Hotel Window (1955), New York Office (1963), and Sun in an Empty Room (1963). These paintings continued to reflect his signature themes of isolation, stillness, and introspection.

Hopper passed away on May 15, 1967, at the age of 84, in his Washington Square home in New York City. He was buried in his hometown of Nyack. Josephine died less than a year later and bequeathed both her works and Hopper’s to the Whitney Museum, ensuring that their legacy would remain intertwined in the history of American art.