Table of Contents

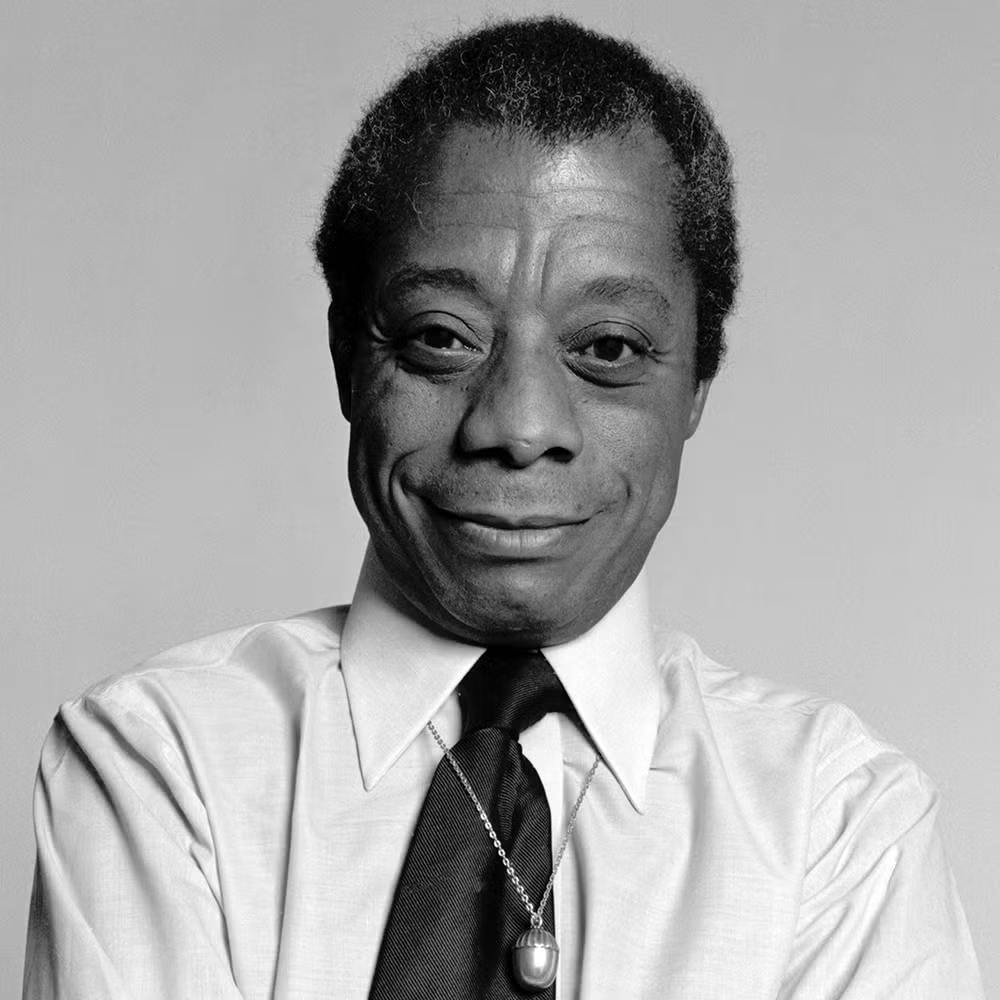

Who Was James Baldwin?

James Baldwin, an influential writer and playwright, gained widespread recognition for his 1953 novel Go Tell It on the Mountain, which explored profound themes of race, spirituality, and humanity. Baldwin’s literary body of work includes iconic novels such as Giovanni’s Room, Another Country, and Just Above My Head, alongside powerful essays like Notes of a Native Son and The Fire Next Time. His writings have had a lasting impact, particularly in the areas of racial and social justice, establishing him as one of the 20th century’s most important and thought-provoking authors.

Early Life

James Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924, in Harlem, New York, to a young single mother, Emma Jones. His biological father’s identity remains unknown, as his mother never revealed the name. At the age of three, Baldwin’s mother married David Baldwin, a Baptist minister, who became a significant influence in his life. Despite their strained relationship, Baldwin regarded David Baldwin as his father and followed in his footsteps by serving as a youth minister in a Harlem Pentecostal church from ages 14 to 16.

Baldwin developed a love for reading at a young age and demonstrated a natural talent for writing. He attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he worked alongside future renowned photographer Richard Avedon on the school’s magazine. Baldwin published several poems, short stories, and plays, displaying a sophisticated grasp of literary techniques uncommon for someone of his age.

After graduating from high school in 1942, Baldwin’s plans for higher education were put on hold as he sought to support his family, which included seven younger siblings. He took on various jobs, including working as a laborer for the U.S. Army in New Jersey, laying railroad tracks. During this time, Baldwin faced pervasive racial discrimination, frequently being denied service at restaurants, bars, and other public spaces due to his race. After losing his job in New Jersey, Baldwin’s struggle to make ends meet deepened, marking the beginning of his lifelong exploration of racial issues and identity through his writing.

Aspiring Writer

On July 29, 1943, James Baldwin faced a profound personal loss with the death of his father, a moment that also marked the arrival of his eighth sibling. Shortly thereafter, Baldwin relocated to Greenwich Village, a vibrant New York City neighborhood that was a hub for artists and writers.

Determined to become a writer, Baldwin supported himself by taking on various odd jobs while devoting his energy to writing a novel. His efforts soon paid off when he befriended the renowned writer Richard Wright, who helped him secure a fellowship in 1945, providing Baldwin with the financial support needed to continue his work. As his career progressed, Baldwin’s essays and short stories began to appear in prominent national periodicals, including The Nation, Partisan Review, and Commentary.

In 1948, Baldwin made a life-changing decision to move to Paris on another fellowship. This relocation allowed Baldwin the space to reflect on his personal experiences and his racial identity. He later remarked to The New York Times, “Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean, I see where I came from very clearly… I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both.” This move marked the beginning of his life as a “transatlantic commuter,” dividing his time between the United States and France.

‘Go Tell It on the Mountain’

Baldwin’s literary breakthrough came in 1953 with the publication of his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. The novel, which was loosely based on Baldwin’s own experiences, tells the story of a young man in Harlem who struggles with his relationship to his father and his religious upbringing. Baldwin later explained, “Mountain is the book I had to write if I was ever going to write anything else. I had to deal with what hurt me most. I had to deal, above all, with my father.”

Gay Literature

In 1954, Baldwin was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which provided him with the financial freedom to continue his writing. The following year, he published Giovanni’s Room, a novel that broke new ground with its complex portrayal of homosexuality, a subject that was still considered taboo at the time. The book tells the story of an American man living in Paris and explores themes of love and identity.

Baldwin would continue to address themes of love and sexuality in his later works, including Just Above My Head (1978), which examines love between men, and Another Country (1962), which explores interracial relationships. Baldwin was forthright about his sexuality and his relationships with both men and women, rejecting rigid categories and emphasizing the fluidity of human sexuality. In a 1969 interview, he stated, “If you fall in love with a boy, you fall in love with a boy,” challenging the narrow views on sexuality prevalent in American society and arguing that such perspectives reflected a limited and stagnant worldview.

Nobody Knows My Name

James Baldwin also ventured into playwriting, most notably with The Amen Corner, a work that explored the phenomenon of storefront Pentecostal religion. The play, which was first produced at Howard University in 1955, later made its way to Broadway in the mid-1960s.

However, it was Baldwin’s essays that solidified his reputation as one of the preeminent writers of his time. Through works such as Notes of a Native Son (1955) and Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961), Baldwin offered an unflinching and deeply personal exploration of the Black experience in America. Nobody Knows My Name became a bestseller, selling over a million copies, and positioned Baldwin as one of the foremost voices of the Civil Rights Movement. Although not an activist in the traditional sense of marches or sit-ins, Baldwin’s writing on race and identity made a profound impact, engaging readers with its nuanced and compelling insight.

The Fire Next Time

In 1963, Baldwin’s work took a pivotal turn with The Fire Next Time, a collection of essays aimed at educating white Americans about what it meant to be Black in America. Baldwin’s essays offered white readers a mirror through which to view themselves, while presenting an unvarnished portrayal of race relations. Despite the harsh truths Baldwin revealed, he remained hopeful about the possibility of societal change. His now-famous declaration, “If we…do not falter in our duty now, we may be able…to end the racial nightmare,” resonated deeply with a wide audience, and The Fire Next Time sold over a million copies.

That same year, Baldwin was featured on the cover of Time magazine, which praised him as the writer who “expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South.” Baldwin’s work during this period continued to shine a light on the racial tensions of America, and he followed The Fire Next Time with the 1964 play Blues for Mister Charlie, which was loosely based on the tragic murder of Emmett Till in 1955.

In 1964, Baldwin also released Nothing Personal, a photographic collaboration with Richard Avedon, which served as a tribute to civil rights leader Medgar Evers. Additionally, he published Going to Meet the Man, a collection of short stories that reflected his ongoing engagement with race and identity.

Later Works and Death

By the early 1970s, Baldwin’s writing began to reflect a growing sense of despair over the state of racial relations in America. Having witnessed the assassinations of figures like Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr., Baldwin’s work began to take on a more strident tone, particularly in his 1972 collection No Name in the Street. This shift in his writing also extended to his efforts in film, as he worked on adapting The Autobiography of Malcolm X for the screen.

While Baldwin’s fame as a literary figure waned somewhat in his later years, he continued to produce significant work across multiple genres. In 1983, he published a collection of poetry titled Jimmy’s Blues: Selected Poems, and in 1987, he released the novel Harlem Quartet. His 1985 book, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, examined the Atlanta child murders, adding another layer to his exploration of race and social injustice.

Baldwin remained an astute observer of American culture, and in his final years, he shared his views as a college professor, teaching at institutions such as the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and Hampshire College.

James Baldwin died on December 1, 1987, at his home in St. Paul de Vence, France. He consistently resisted the label of spokesperson or leader, preferring to view his role as one of bearing “witness to the truth.” Through his profound and lasting literary legacy, Baldwin fulfilled this mission and cemented his place as one of the most influential voices of the 20th century.