Table of Contents

Who Was Jelly Roll Morton?

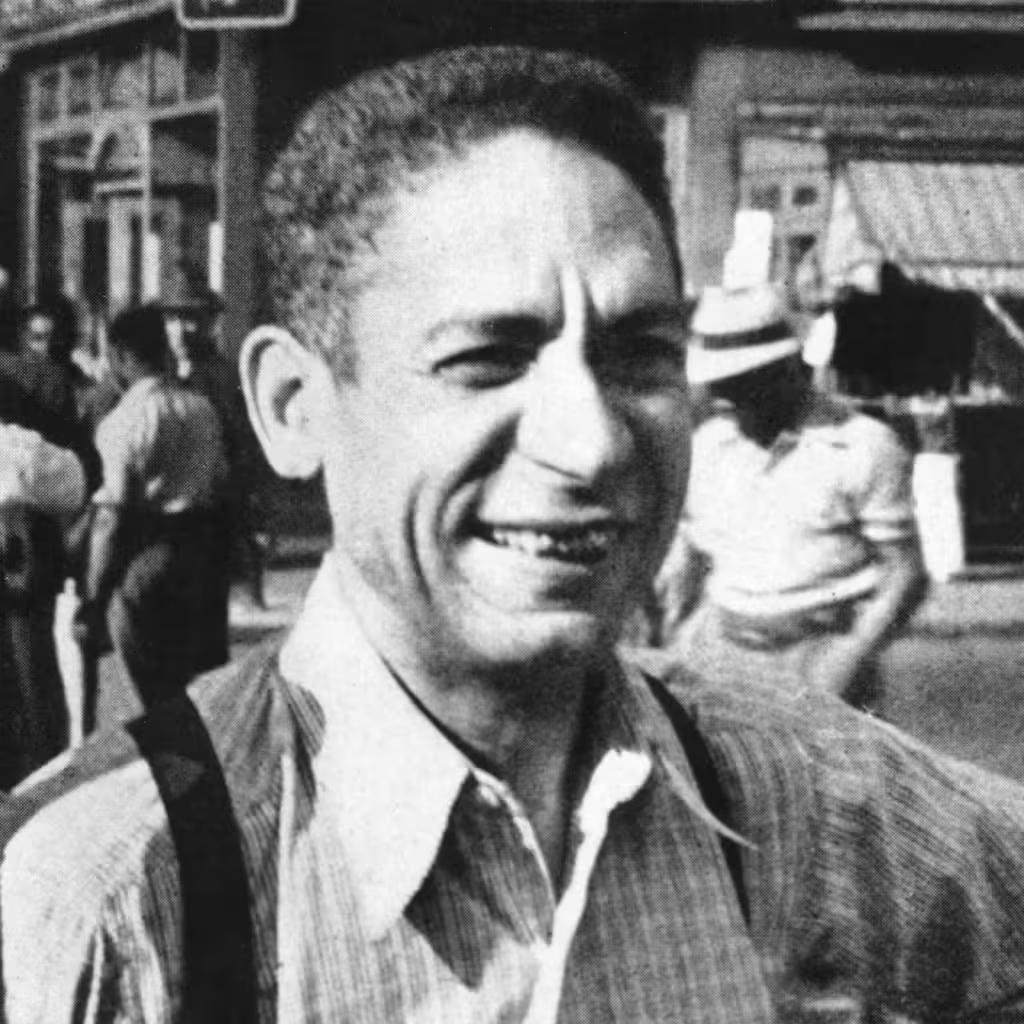

Jelly Roll Morton, a pioneering figure in the early development of jazz, began his musical career playing piano in the bordellos of New Orleans. As one of the first jazz innovators, Morton gained widespread recognition in the 1920s as the leader of Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers. His music, which blended ragtime, minstrelsy, and dance rhythms, helped shape the foundation of jazz. Though his career waned in the 1930s, Morton’s contributions to the genre were reignited in a series of interviews for the Library of Congress, just before his death on July 10, 1941, in Los Angeles, California.

Early Years

Ferdinand Joseph Lamothe, later known as Jelly Roll Morton, was born on October 20, 1890 (although some sources cite 1885) in New Orleans, Louisiana. The son of racially mixed Creole parents—of African, French, and Spanish descent—Morton took the surname of his stepfather. He began playing the piano at age 10, and by his teenage years, he was performing in the city’s red-light district, where he earned the nickname “Jelly Roll.” A talented musician, Morton was at the forefront of a musical revolution, blending ragtime, minstrelsy, and the emerging sounds of jazz.

National Star

As a teenager, Morton left home and embarked on a life of travel, earning a living as a musician, vaudeville performer, gambler, and even a pimp. Known for his bold personality, Morton often claimed to have “invented jazz,” a statement that, while exaggerated, reflected his innovative role in the genre. He is credited with being the first jazz musician to transcribe his compositions, with Original Jelly Roll Blues being one of the first published jazz works.

In 1922, Morton moved to Chicago, where he made his first recordings the following year. By 1926, he formed the Red Hot Peppers, a band that became renowned for its lively and sophisticated New Orleans-style jazz. Hits like Black Bottom Stomp and Smoke-House Blues brought the group national acclaim and laid the groundwork for the swing era that followed. During this time, Morton showcased his exceptional skills as both a composer and pianist.

In 1928, Morton relocated to New York, where he continued recording, producing tracks such as Kansas City Stomp and Tank Town Bump. While he incorporated elements of modern jazz, such as harmonized ensembles and improvisational solos, his music remained deeply rooted in New Orleans traditions. Unfortunately, as jazz evolved during the late 1920s, Morton’s style was viewed as increasingly outdated. The Great Depression further strained his finances, and he fell into obscurity. Despite this, Morton’s legacy as a foundational figure in jazz history remains undisputed.

Late Career, Death, and Legacy

In the late 1930s, while managing a jazz club in Washington, D.C., Morton crossed paths with folklorist Alan Lomax. In 1938, Lomax began recording a series of interviews with Morton for the Library of Congress, where Morton provided an oral history of jazz’s origins and demonstrated its early styles on the piano. These recordings played a key role in revitalizing interest in Morton and his contributions to jazz. However, his declining health hindered any substantial comeback, and he passed away in Los Angeles on July 10, 1941.

While Morton may not have been the sole inventor of jazz, he is widely regarded as one of its greatest innovators. His influence continues to be recognized, with posthumous honors including his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005, both testaments to the enduring legacy of his musical impact.