Table of Contents

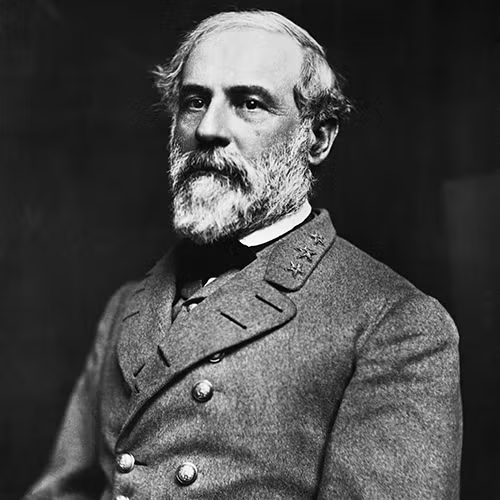

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert E. Lee was a prominent Confederate general during the U.S. Civil War, commanding the armed forces of his home state, Virginia, and later becoming the general-in-chief of the Confederate Army. Though the Confederacy ultimately lost the war, Lee gained renown for his military strategy, securing several key victories on the battlefield. After the war, he became president of Washington College, which was later renamed Washington and Lee University in his honor following his death in 1870.

Early Life

Born on January 19, 1807, at Stratford Hall in Virginia, Robert Edward Lee came from an influential family. His father, Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, was a Revolutionary War hero, and his extended family included a U.S. president, a chief justice, and signers of the Declaration of Independence. Lee followed in his father’s footsteps by enrolling at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated second in his class in 1829, without a single demerit. He excelled in military studies, particularly in artillery, infantry, and cavalry tactics.

Family Life

In 1831, Lee married Mary Custis, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington. The couple settled at the Arlington plantation in Virginia, which Mary inherited after her father’s death in 1857. They had seven children—four daughters and three sons—who all became involved in the Confederate cause during the Civil War.

When the Civil War began, Union troops occupied the Arlington estate, and the federal government seized the land. It was later turned into Arlington National Cemetery, one of the most hallowed grounds in America.

Early Military Career

After graduation, Lee’s military career took him across the United States, including posts in St. Louis, New York, and Savannah. He gained national recognition during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), where he served under General Winfield Scott. Lee’s leadership and tactical acumen earned him accolades, with Scott even suggesting that the U.S. government take out a life insurance policy on him.

Despite his military successes, Lee struggled with non-combat duties. After his military service, he briefly managed his father-in-law’s struggling estate at Arlington. His time spent overseeing the plantation left him disillusioned with civilian life.

Robert E. Lee and Slavery

Although Lee did not own slaves in his youth, he and his wife inherited enslaved people from both of their families. Lee’s views on slavery were complex and reflective of his time. While he acknowledged the moral and political wrongs of slavery, he held racist beliefs and considered slavery necessary for maintaining social order in the South.

As executor of his father-in-law’s estate, Lee was responsible for managing the enslaved people on the Arlington plantation. Though he freed some of them in accordance with his father-in-law’s will, Lee’s actions toward the rest, including reports of mistreatment, have been widely criticized. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, Lee continued to seize freed Black people from Union territories and send them into slavery. Near the end of the war, he supported the idea of using enslaved individuals in the Confederate Army in exchange for their freedom, though the policy was never implemented.

Leadership in the Confederacy

In 1859, Lee gained national attention when he was sent to suppress John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry. His success in quelling the rebellion brought him recognition as a capable military leader. When the Civil War began, Lee’s loyalty to his home state of Virginia led him to resign from the U.S. Army and join the Confederate cause, despite initial offers to command Union forces.

Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia in 1862, where he achieved significant victories, such as the Seven Days Battles and the Second Battle of Bull Run. However, his fortunes changed with the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single-day battle of the war, which ended in a strategic defeat for Lee.

The Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 marked a turning point in the war. Lee’s defeat, along with the significant loss of his troops, halted his invasion of the North and bolstered Union morale.

The End of the War and Surrender

By 1864, Union General Ulysses S. Grant had gained the upper hand, and Lee’s position became increasingly untenable. After abandoning Richmond in April 1865, Lee, aware that the Confederacy was nearing collapse, reluctantly surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

Post-War Life and Death

Following the war, Lee was spared harsh punishment by President Abraham Lincoln and General Grant. He returned to his family and later became president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. Under his leadership, the college’s enrollment and financial standing improved.

Lee suffered a stroke in September 1870 and died on October 12 of that year, surrounded by family. He was buried at Washington College, which was renamed Washington and Lee University in his memory.

Legacy and Controversy

Lee’s legacy has been a subject of intense debate. For many in the South, he became a symbol of honor and resistance. Monuments to Lee were erected across the South, and his birthday was celebrated in several states. However, his role in the Confederacy and his defense of slavery have sparked significant controversy, especially in the 21st century.

The removal of Lee’s statues, particularly in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, sparked protests and violence, reflecting the ongoing tensions surrounding his legacy. Some view his commemoration as a reminder of Southern heritage, while others argue that it symbolizes a painful and oppressive history.

Robert E. Lee in Popular Culture

Lee has been the subject of numerous books, documentaries, and films, with notable portrayals in the novel The Killer Angels by Jeffrey Shaara, which was adapted into the 1993 film Gettysburg. The film depicted Lee as a complex and strategic figure, and later adaptations, such as Gods and Generals (2003), continued to explore his role in the Civil War. These portrayals contribute to the ongoing debate about his legacy in American history.