Table of Contents

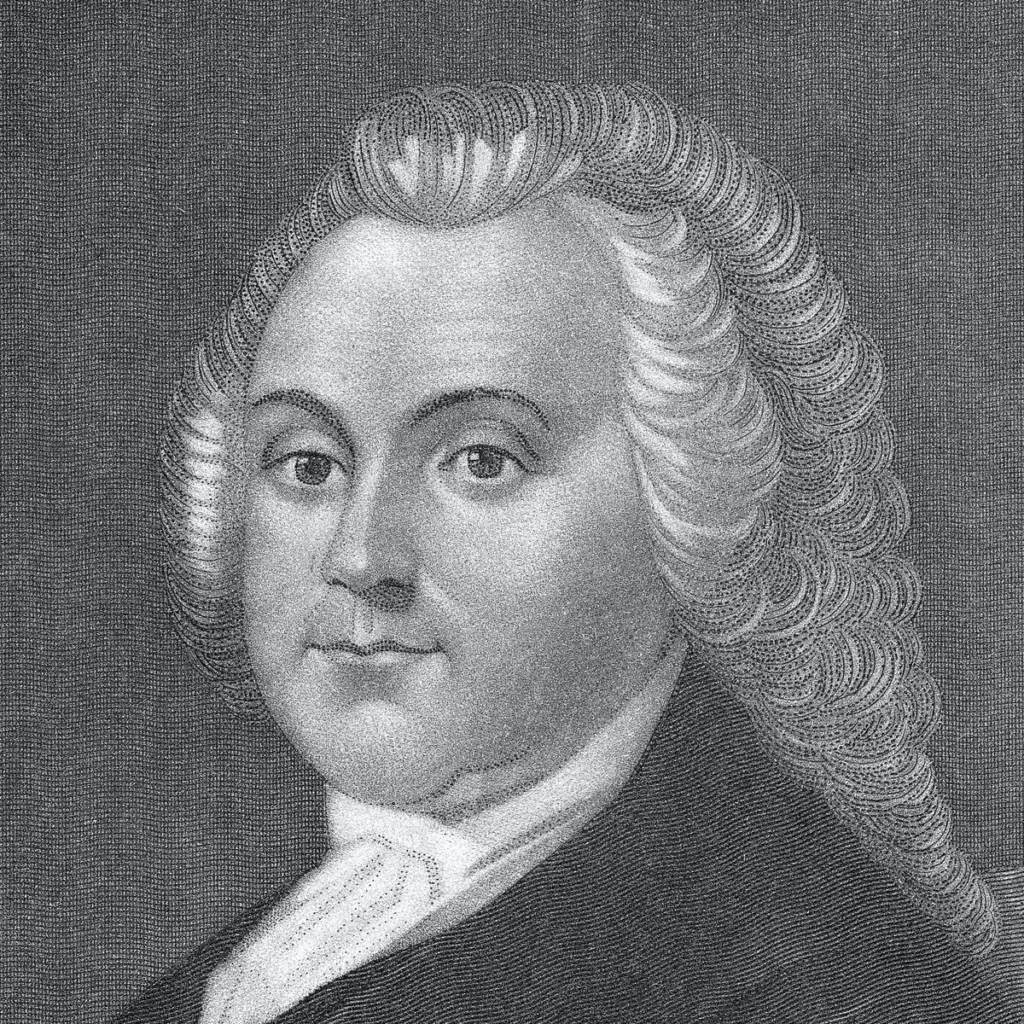

Who Was Roger Williams?

Roger Williams, an influential figure in early American history, was a staunch advocate for religious freedom and the separation of church and state. After completing his education in England, he traveled to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, initially with the intent to serve as a missionary. However, his radical views on religious liberty and his opposition to the colonial practice of seizing land from Native Americans led to his exile from the colony. In 1636, Williams and his followers established a new settlement in Narragansett Bay, where he purchased land from the Native American Narragansett tribe. This colony became a sanctuary for religious minorities, including Baptists, Quakers, Jews, and others seeking refuge from religious persecution. Williams’s pioneering ideas on religious freedom would later influence the framers of the U.S. Bill of Rights, nearly a century after his death.

Early Life

Although his birth records were lost in the Great Fire of London in 1666, it is believed that Roger Williams was born in early 1603. His father, James Williams, was a successful merchant, and his mother, Alice, raised him in the Anglican Church. Growing up amidst the religious tensions of King James I’s reign, Williams developed a strong belief in religious and civic liberty. As a young man, Williams attracted the attention of Sir Edward Coke, a renowned English lawyer, who supported his education. This led to Williams’s enrollment at Charterhouse School in London, where he excelled in languages, mastering Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Dutch, and French. His linguistic skills earned him a scholarship to Pembroke College at Cambridge University. Upon graduation in 1627, Williams entered holy orders within the Church of England. However, he soon converted to Puritanism, distancing himself from the Anglican Church.

A Challenge to Faith and Life in a New Land

In December 1629, Roger Williams married Mary Bernard, and the couple had six children. After leaving Cambridge, Williams served as chaplain to Sir William Masham, which brought him into contact with notable Puritan political leader Oliver Cromwell. By 1630, Williams had become disillusioned with the Church of England, which he considered corrupt, and adopted Separatist views, asserting that true religion could only be known when Christ himself returned to establish it.

In 1631, Williams and his wife sailed to America, hoping to test his faith in the New World. Initially arriving in Boston with the intention of becoming a missionary to the Native Americans, Williams immersed himself in learning their language, culture, and religious practices. His empathy for their plight led him to challenge the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s practice of granting land charters to settlers, arguing that land could only be legitimately acquired through direct purchase from the Native Americans.

Williams’s amiable personality made him well-liked in many circles, but his impulsive nature and strong convictions often led to conflicts with colonial authorities. Over the next six years, his advocacy for a strict separation of church and state put him at odds with the Puritans, who believed that religious and civil matters should be intertwined and enforced by the government. As a result, Williams was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, setting the stage for his founding of Providence Plantation, a colony built on principles of religious freedom and self-governance.

Banishment

In 1635, the magistrates of the Massachusetts Bay Colony had reached their breaking point with Roger Williams, accusing him of sedition and heresy. As a result, he was banished from the colony. Seeking refuge, Williams and his followers fled to Narragansett Bay, where they formed an alliance with a local Native American tribe. There, Williams established the settlement of Providence, named for divine guidance. Within a few years, Providence became a sanctuary for other religious dissenters, including Anne Hutchinson.

Despite his exile, Williams continued to face hostility from religious purists in neighboring Massachusetts, who feared his growing influence and threatened to seize control of Providence. Rejecting the claim that the English crown had the right to grant charters to land that he believed rightfully belonged to Native Americans, Williams made two trips to England to secure a charter for his colony. His efforts were successful, and upon returning to Providence, he established a thriving trading post and fostered strong relationships with the Native American tribes. Through these efforts, he became known as a peacemaker, navigating territorial disputes while promoting his ideals of religious tolerance and personal conviction. Rhode Island eventually became a haven for Baptists, Quakers, and Jews.

Later Life and Death

In the 1670s, relations between settlers and Native Americans in New England rapidly deteriorated, despite Williams’ continued attempts at peace. The outbreak of King Philip’s War in 1675, fueled by tensions over land encroachment and the devastating impact of disease on Native populations, further strained these relationships. In his 70s, Williams was elected captain of the Providence militia, yet he saw his efforts at reconciliation unravel as the town was burned in March 1676.

Despite these challenges, Williams lived to see Providence rebuilt and witnessed the continued growth of Rhode Island as a colony. He remained active in preaching and was proud of the colony’s success. Williams passed away in early 1683, largely unacknowledged by the local community. He was buried on his property, and over time, his farm fell into disrepair. Attempts to locate his grave nearly two centuries later yielded no results, save for an old tree root. His remains are now preserved by the Rhode Island Historical Society.

Although his death went largely unnoticed at the time, Williams’ legacy gained significant recognition in the early days of the American Revolution. His staunch advocacy for religious freedom and the principle of “a wall of separation” between church and state were later enshrined in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, cementing his role as a foundational figure in the fight for religious liberty.