Table of Contents

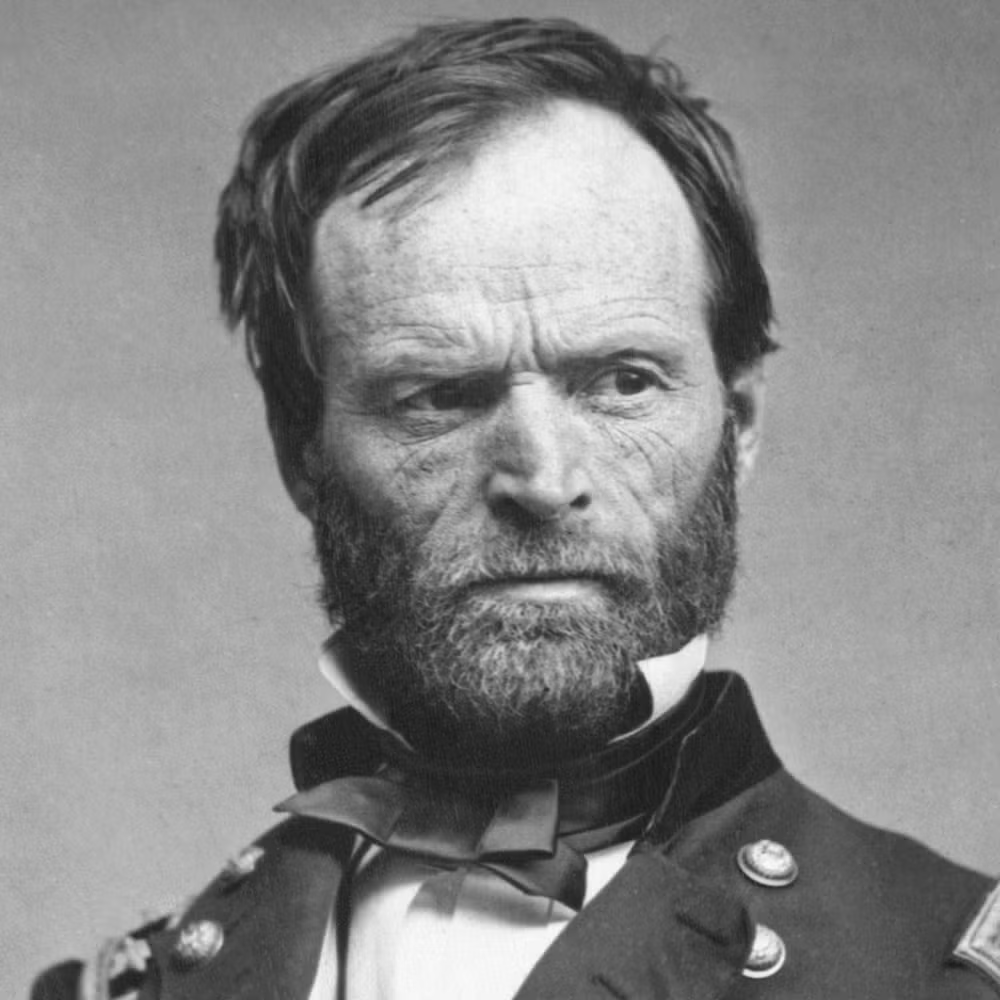

Who Was William Tecumseh Sherman?

William Tecumseh Sherman is a significant figure in American military history, known for his impactful leadership during the Civil War. His early military career was fraught with challenges, including a temporary relief from command. However, he marked a turning point in his career with a triumphant return at the Battle of Shiloh. Following this victory, Sherman commanded a force of 100,000 troops, leading a destructive campaign against Atlanta and implementing his infamous “March to the Sea,” which ravaged the state of Georgia. Often associated with the phrase “war is hell,” Sherman is regarded as a key architect of modern total war.

Early Life

Sherman was born on February 8, 1820, in Lancaster, Ohio, into a prominent family as one of eleven children. His father, Charles Sherman, was a successful lawyer and served as an Ohio Supreme Court justice. The untimely death of his father when Sherman was just nine years old left the family in a precarious financial situation. Consequently, he was raised by a family friend, Thomas Ewing, who was a U.S. senator from Ohio and a notable member of the Whig Party. There has been considerable speculation regarding the origin of Sherman’s middle name. In his memoirs, he recounted that his father named him William Tecumseh out of admiration for the Shawnee chief.

Early Military Career

In 1836, Senator Ewing facilitated an appointment for William Tecumseh Sherman to the United States Military Academy at West Point. During his time at the academy, Sherman distinguished himself academically but displayed a notable disregard for the demerit system. Although he avoided significant disciplinary action, his record included numerous minor offenses. He graduated in 1840, ranking sixth in his class. Sherman’s early military engagements began with action against the Seminole Indians in Florida, followed by various assignments in Georgia and South Carolina, where he became acquainted with many prominent families of the Old South.

Sherman’s initial military career was relatively unremarkable. Unlike many contemporaries who participated in the Mexican-American War, he was stationed in California as an executive officer during this conflict. In 1850, he married Eleanor Boyle Ewing, the daughter of Thomas Ewing. Feeling that his prospects in the U.S. Army were limited due to his lack of combat experience, Sherman resigned his commission in 1853. He subsequently remained in California during the gold rush, working as a banker until the Panic of 1857 led to the bank’s failure. Following this setback, he attempted to practice law in Kansas but met with limited success. By 1859, Sherman had assumed the role of headmaster at a military academy in Louisiana, where he demonstrated effective administrative skills and garnered community respect. As sectional tensions intensified, Sherman cautioned his secessionist acquaintances about the potential for a prolonged and bloody conflict, predicting that the North would ultimately prevail. After Louisiana seceded from the Union, he resigned and relocated to St. Louis, hoping to avoid involvement in the impending conflict. Although he held conservative views on slavery, he remained a staunch supporter of the Union. Following the attack on Fort Sumter, Sherman sought assistance from his brother, Senator John Sherman, to secure a commission in the Army.

Service in the Civil War

In May 1861, Sherman was appointed as a colonel in the 13th U.S. Infantry and assigned to command a brigade under General William McDowell in Washington, D.C. He participated in the First Battle of Bull Run, where Union forces suffered a significant defeat. Subsequently, he was transferred to Kentucky, where his outlook on the war became increasingly pessimistic. Sherman expressed concerns to his superiors about supply shortages while exaggerating the strength of enemy forces, ultimately leading to his being placed on leave and deemed unfit for duty. His struggles were widely publicized, with some media outlets labeling him as “insane,” a characterization believed to stem from a nervous breakdown.

In mid-December 1861, Sherman returned to active duty in Missouri, receiving rear-echelon assignments. In Kentucky, he provided logistical support for Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant during the successful capture of Fort Donelson in February 1862. The following month, Sherman was assigned to serve with Grant in the Army of West Tennessee, where he faced his first significant test as a combat commander at the Battle of Shiloh.

Initially dismissing intelligence reports regarding Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s presence in the area, Sherman took insufficient precautions to bolster picket lines or deploy reconnaissance patrols. On the morning of April 6, 1862, Confederate forces launched a fierce assault. In response, Sherman and Grant rallied their troops, ultimately repelling the Confederate offensive by the end of the day. With reinforcements arriving that evening, Union forces mounted a counter-attack the next morning, scattering the Confederate troops. This experience forged a lasting friendship between Sherman and Grant.

Sherman continued to serve in the West, working alongside Grant in the protracted campaign against Vicksburg. However, relentless media criticism targeted both leaders, with one newspaper lamenting that the “Army was being ruined in mud-turtle expeditions, under the leadership of a drunkard [Grant] whose confidential adviser [Sherman] was a lunatic.” Ultimately, Vicksburg fell, and Sherman was entrusted with command over three armies in the West.

Evolving Toward “Total War”

In February 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman initiated a strategic campaign from Vicksburg, Mississippi, aimed at dismantling the vital rail hub at Meridian and eliminating Confederate resistance in central Mississippi. Meridian’s significance lay in its position at the intersection of three critical railroad lines, situated between Jackson, the state capital, and Selma, Alabama, known for its cannon foundry and manufacturing facilities. Given the urgency of the campaign, Sherman’s forces disrupted supply lines from Vicksburg and relied on foraging to sustain themselves.

Confronted by Confederate General Leonidas Polk, who commanded approximately 10,000 troops, Sherman’s overwhelming force of 45,000 Union soldiers easily overcame initial resistance. As Sherman advanced westward, he skillfully employed feint tactics to distract and hinder Polk’s forces, which were tasked with defending Mobile, Alabama. On February 11, 1864, Sherman’s troops successfully attacked and destroyed the railroad center at Meridian, subsequently dispersing detachments in four directions to obliterate railroad tracks, bridges, trestles, and any train equipment in their path. This operation served as a precursor to Sherman’s renowned “March to the Sea” in Georgia and marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of military strategy during the Civil War, signaling a shift toward the concept of “total war.”

By early September 1864, Confederate Lieutenant General John Bell Hood found himself under siege and was compelled to evacuate Atlanta, leaving behind as much of their supplies and munitions as they could. After securing the city, Sherman ordered its destruction. With a force of 60,000 men, he commenced his famous “March to the Sea,” carving a 60-mile-wide swath of devastation across Georgia. Sherman understood that in order to win the war and preserve the Union, his army needed to dismantle the South’s will to resist. This approach, characterized by the systematic destruction of infrastructure and resources, exemplified his military strategy of “total war.”

When Ulysses S. Grant assumed the presidency in 1869, Sherman was appointed as the commanding general of the U.S. Army. In this capacity, one of his responsibilities was to protect the construction of railroads from Native American attacks. Viewing Native Americans as obstacles to progress, Sherman advocated for the complete destruction of hostile tribes. Despite his harsh stance on Native Americans, he also condemned the exploitation of these communities by unscrupulous government officials on reservations.

Life After War and Death

In February 1884, Sherman retired from the Army and initially settled in St. Louis before relocating to New York in 1886. During his retirement, he engaged in various pursuits, including theater, amateur painting, and public speaking at dinners and banquets. He famously declined to seek the presidency, asserting, “I will not accept if nominated, and will not serve if elected.”

Sherman passed away on February 14, 1891, in New York City. Following his wishes, he was interred at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis. In honor of his contributions, President Benjamin Harrison ordered all national flags to be flown at half-staff. Although Sherman faced considerable criticism in the South, where he was often demonized for his wartime actions against civilians, historians regard him highly as a military strategist and astute tactician. He profoundly transformed the nature of warfare, recognizing its inherent brutality when he stated, “War is hell.”